December 2, 2025

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

Executive Summary

The Strategic Reality: The legal profession is unknowingly participating in a $300+ billion AI infrastructure war between OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, and others. This isn't about choosing productivity tools—it's about aligning with technology ecosystems that will determine how law is practiced for the next decade.

The Triple Bind:

Adopt an AI platform → Lock yourself into an ecosystem with uncertain exit costs

Experiment without governance → Fragment your data across vendors while fueling their competitive spend

Refuse to adopt AI → Accept declining productivity that approaches malpractice as competitors accelerate

Critical Risks for Legal Practice:

Data as ammunition: Every client document and prompt feeds model improvement, even in "enterprise" tiers that promise no training use but retain data for "analytics"

Circular capital trap: Microsoft, Amazon, and Google are both investors in and infrastructure providers to AI companies, creating unprecedented counterparty risk concentration

Regulatory fragmentation: The same AI deployment can be high-risk in the EU, unregulated in parts of the US, and require licensing in China

The Investment Reality: Hyperscalers are spending billions annually on AI infrastructure, with complex circular investments. This creates "too interconnected to fail" dynamics that make vendor selection a long-term strategic commitment.

Action Items:

Evaluate AI vendors for exit rights, not just capabilities

Maintain tool-agnostic architectures where possible

Create approved tool lists with clear data governance rules

Document AI dependencies before they become invisible infrastructure

Control your knowledge bases separately from any vendor's platform

Bottom Line: You cannot avoid this war. Maintain strategic flexibility through conscious vendor selection, smart exit planning, and governance structures that prevent accidental lock-in. Your first priority needs to be preserving your firm's autonomy while the giants fight around you.

We've Been Here Before

In the early 1980s, dozens of computer manufacturers fought for dominance. Commodore, Atari, Tandy, Apple, IBM, Amiga and others all tried to become the standard. By the mid-1990s, only two ecosystems really mattered. Windows PCs and Macs. The consolidation was not really about who had the “best” hardware. It was about ecosystems and inertia. Software libraries. Developer support. Compatibility. Procurement officers who simply bought what everyone else was buying. Once firms filled their offices with IBM-compatible PCs and WordPerfect, then later Word, the cost of switching became enormous. You could move, but only by re-training staff, abandoning years of software investment, and renegotiating vendor relationships.

The boardrooms of Silicon Valley are staging a replay of the 1980s, and most lawyers are watching from the cheap seats without realizing they are already picking sides. Every time your firm turns on Copilot, rolls out CoCounsel, or subscribes to Spellbook, you are not adopting a neutral productivity tool. You are quietly aligning your practice with a particular AI ecosystem. You are casting a vote in the most expensive war the world has ever seen.

And here is the most uncomfortable part:

If you pick a tool, you are casting a vote.

If you switch between tools you are fueling the war.

And if you do not pick a tool, refusing to use AI, you are reducing your productivity, and limiting your firm to a point approaching malpractice.

Let me explain. When a firm standardizes on a single AI platform, it casts a clear vote in the AI wars. It trains its people, builds workflows, and tunes everything around that vendor’s models and quirks. That is the classic lock-in story.

But refusing to pick, letting everyone “experiment” with whatever looks interesting this week, is not neutral either. When lawyers bounce between tools, uploading documents, tweaking prompts, and comparing outputs, they are supplying the ammunition for this conflict. You are providing engagement metrics that vendors use to justify ever larger investments and ever deeper integration into an AI platform. Plus, the firm still drifts toward an ecosystem. It just does so without intention, or a plan for how to exit.

And perhaps most unfortunate of all, if you attempt to stay neutral by not using AI, you are making your productivity a casualty of this war because your failure to adopt AI and increase productivity will amount to losing ground. As others improve their productivity by incorporating AI safely, you will appear slower.

I’m not suggesting you stay out of this war. Rather, this article is about making your votes in this war deliberately and intelligently. We will map the main factions in the AI wars, show how their strategies create real legal risk on confidentiality, privilege, regulation, and vendor dependence, and lay out practical steps for lawyers to get the benefits of AI without either locking themselves into the wrong camp or unknowingly fueling a war they do not control.

The Battlefield You Just Walked Onto

There is a battle raging around you. One of the most well-funded, globally fought, intelligent battles. Here's what you need to know about it.

The Armies of the AI War

Underneath the glossy apps and legal-specific tools, a small set of frontier models is fighting for dominance. Right now, most of the legal tech you use is merely a frontier model with a specific wrapper. It costs hundreds of millions of dollars to develop and train an LLM—the engine for AI tools. Only companies with deep capital reserves or very committed strategic backers can even step onto this field. That is why there are so few serious contenders today and why the number is likely to shrink as the AI arms race continues. The frontier models include OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google Gemini, Meta’s Llama, xAI’s Grok, and a handful of other smaller ones such as Mistral and Deepseek.

These foundational models sit beneath almost everything lawyers now see in the market. Microsoft Copilot rides on OpenAI. Vincent AI from vLex relies on a blend of Claude, OpenAI, Llama, and Gemini. Spellbook used to market itself as “ChatGPT for contracts.” The vast majority of other legal-specific tools are wrappers on top of the same small set of engines.

And around each frontier model sits an ecosystem. This ecosystem is made up of other applications and AI tools that connect with the frontier model. This ecosystem is held together through application programming interfaces, commonly known as APIs. An API is simply a structured way for one piece of software to ask another piece of software to do something and to get a predictable answer back.

The frontier models are making decisions and alliances that extend far beyond the AI outputs your lawyers see. When you use a legal tool that is built on top of one of these frontier models you are deciding which army gets your data, your financial support, and your institutional knowledge. Even if you have paid a premium for privacy, there is still a lot of knowledge to be gleaned from your usage patterns.

Information as Ammunition

If the models are the armies, information is their ammunition and armor. They improve only when they ingest more data and get better feedback. That means human language, documents, code, images, clicks, corrections, and ratings. Reinforcement learning from human feedback, adversarial testing, multimodal grounding, and ordinary daily use all push these systems forward.

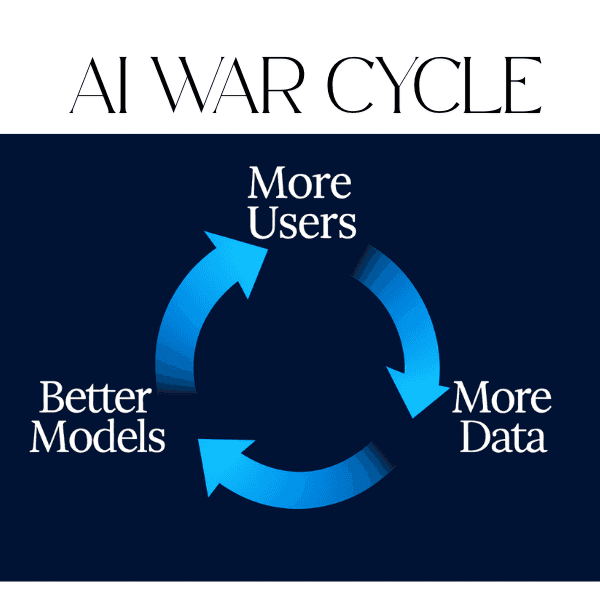

The dynamic is simple. More users bring more data. More data yields better models. Better models attract even more users. Scale turns into quality, which then turns into more scale.

This need for information explains some of the uglier privacy choices we are already seeing. OpenAI has billions of ChatGPT conversations refining its next models. Google has search histories, Gmail, and YouTube behavior feeding Gemini. Grok drinks from X. Meta has billions of users generating text, images, and social graphs every day, and has made it difficult if not impossible to opt out of its information gathering. Even privacy-conscious Anthropic has now shifted to requiring non-enterprise users to opt-out of data sharing, even though it was built with a vision of safe, privacy-focused AI.

Meta’s Llama strategy shows how far this can go. When Meta updated its privacy policy in Europe in 2024, users learned that their posts, photos, and even some private messages could be used to train Llama unless they went through a formal objection process. Meta relied on “legitimate interest” under the GDPR rather than asking for explicit consent. Meta knows it's open-weight model cannot easily monetize through API fees. Its return on investment depends on ad targeting, engagement, and staying competitive in the model race. Without a constant flow of fresh user data, Llama falls behind. And if Llama falls behind, Meta loses its place in the war.

Many users have no idea that their prompts, photos, videos, and social interactions are feeding tomorrow’s models. For lawyers, the stakes are higher. Every time client material leaves your controlled environment and passes through third-party systems, you are potentially handing ammunition to some army, along with all of the attendant confidentiality, privilege, and regulatory implications that follow.

Capital and Compute Decide Who Survives

The AI wars are also shaped by inflexible bottlenecks in hardware and infrastructure. Large models need the fastest chips and massive cloud capacity. Nvidia’s chips and GPUs are the current standard. They are produced in limited places and already wired deeply into many training pipelines. Switching away from Nvidia often means redesigning systems, rewriting code, and renegotiating contracts. That friction keeps Nvidia embedded at the heart of the conflict.

The largest players are already implementing their own workarounds. Google uses its own custom-created “TPU” (Tensor Processing Unit) chips for Gemini so it would not have to rely on Nvidia’s generic chips. Amazon built specialized Trainium processors that are essentially “AI accelerators” and gave Anthropic early access through the Bedrock platform. Microsoft gives OpenAI priority access to Azure’s cloud infrastructure. These relationships create advantages that smaller competitors cannot easily match.

What if This Really is an AI Bubble?

Market analysts are asking whether the debt-funded build-out of data centers and chips can earn an adequate return, or whether parts of the AI trade now have bubble characteristics.

Lawyers do not need to guess where stock prices will land. The practical lesson is about counterparty risk. Some vendors will consolidate, pivot, or fail. Highly leveraged players may have to cut back on support or change strategy in ways that affect service quality. If your firm or your client has tied core workflows to one model or cloud service, you will have fewer options if a bubble bursts.

Too Big to Fail -- Too Interconnected to Fail

Cloud and internet giants are pouring unprecedented capex (capital expenditures) into AI infrastructure, with estimates that capital spending could reach the mid$300 billions in 2025, largely driven by AI data centers. For example Elon Musk’s xAI just worked out a deal to place a large data center in Saudi Arabia—a strategic location to help extend xAI’s global reach. Nvidia has become the main beneficiary. One recent quarter report showed around $57 billion in revenue and triple-digit year-over-year growth, with its Blackwell chips alone generating $11 billion in a single quarter and dominating high-end GPU shipments. A large share of that spending comes from Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, AWS, Meta, and others, who are racing each other for the greatest compute power, and thereby making Nvidia one of the only clearly cash-profitable companies in this war.

Each of these behemoths in this War has extended its reach by engaging in a practice of circular cashflow and vertical integration.

The Circular Flow of Capital

Big tech platforms (Microsoft, Amazon, Google) pour tens or hundreds of billions into GPUs and custom chips from Nvidia and others, then monetize that capacity by selling cloud and AI services to OpenAI and Anthropic and to enterprise customers. The startups, in turn, sign massive commitments back to those same cloud companies, called hyperscalers.1 Microsoft invested billions into OpenAI, obtaining around a 27% interest in the for-profit version of OpenAI. In turn OpenAI has reportedly committed to spend around $250B on Microsoft’s Azure cloud services. Anthropic has agreed to make AWS its primary training partner and to run its flagship models on Amazon’s Trainium and Inferentia chips.

On top of that, hyperscalers and Nvidia are now co-investing directly into the startups whose workloads they host. Amazon has invested up to $8B in Anthropic in the form of convertible notes, gaining a minority stake, and anchoring Anthropic’s compute on AWS. Google has committed $2B to Anthropic tied to a long-term Google Cloud deal. And most recently Microsoft and Nvidia together agreed to invest up to $15B in Anthropic in exchange for Anthropic buying $30B in Azure capacity powered by Nvidia hardware.

Essentially, money flows like this: investors and customers fund hyperscalers → hyperscalers buy Nvidia and custom chips and build data centers → hyperscalers invest cash and credits into AI startups → startups lock in huge commitments to buy cloud capacity from those same hyperscalers → cash returns to Nvidia and the cloud providers, often boosting their valuations and giving them more capital to restart the cycle.

Anthropic has become an explicit hedging target. Microsoft is committing up to $5 billion and Nvidia up to $10 billion into Anthropic, even as Amazon separately agreed to a deal reported around $30 billion to deepen Anthropic’s use of AWS, giving the startup multiple competing cloud and chip patrons. In practice this means the same dollars that start as Azure or AWS customer spend on AI workloads are recycled into equity in Anthropic, which in turn signs massive longterm compute and infrastructure agreements back with those same clouds and with Nvidia.

This is affecting the average user by determining which AI tools and ecosystems you join, but also in other ways. For example Lenovo, the world’s largest PC maker, is stockpiling memory chips and other components, keeping inventories about 50% higher than normal because AI data centers are gobbling up the same parts that go into everyday computers. That scramble is pushing computer component prices sharply higher and raising the risk of shortages in 2026. For the average user, that means a few likely outcomes. PCs, tablets, and even phones could become more expensive, or manufacturers may ship devices with less memory than you’d otherwise expect for the price. Some models might be harder to find or take longer to ship. In other words, even if you do not use AI yourself, this war will still have an impact.

Whether or not today’s AI boom proves to be a bubble, the real issue for lawyers is how this highly leveraged, tightly interconnected AI stack reshapes the risk profile of both your own systems and your clients’ systems—and what, concretely, that should mean for how you design, buy, and advise on technology.

Why the AI War Matters for Lawyers

As lawyers we do not control the raging AI War. We cannot control an AI bubble. What we do control, however, is how prepared we are, and how we’ve chosen to minimize our exposure if an AI bubble does burst. That means treating AI providers like any other critical infrastructure in a frothy market and building exit ramps and alternatives before we need them.

Ecosystem Gravity and Quiet Lock In

The AI tools you are beginning to rely on are constrained by the bottlenecks and capital structures mentioned above. When you pick an AI tool you are not only choosing your preferred user interface, you’re also likely tying your practice and your clients to companies that are spending staggering amounts on specialized chips and data centers. This spend forces AI companies into needing aggressive data practices and systems that make it difficult to switch AI tools. They do this because they need users and information to justify the current expenditure and future investments.

Refusing to bless any one tool is not neutral. If your firm experiments on various AI tools without guidance, or moves from tool to tool, chasing the latest ‘new thing’, you have cast a vote. You just did it without governance or an exit plan. And the vote you cast was essentially just fuel in the AI war that is raging around us. Plus, you are likely making AI governance more difficult at your firm.

The Ugly Truth About Confidentiality and Data Governance

Your first question when considering any AI tool is simple: “Where does client information go when we use this tool, and what does the provider do with it?” That’s the right question to start with. But your inquiry should not end there.

As discussed above, AI models need your data, as the ammunition in this war. So they find ways around strict privacy commitments. AI tools and specifically enterprise-level offerings often promise that prompts and outputs will not be used for training, but still retain them for support, abuse detection, or analytics. Some AI providers retrain their models using your data, which can make it unclear whether your information is kept private or is included in updates that improve the vendor’s system—even if you have a privacy agreement in place. Others, as with Meta’s Llama strategy, lean on privacy concepts such as legitimate interest to turn user data into fuel and treat investigations and fines as a cost of doing business.

This has obvious implications for privilege and privacy. Policies that say only “do not paste client secrets into free tools” and “don’t use fake citations” are already outdated. to give their lawyers an approved list of models, clarity about where they run and how training flags are set, and contracts and technical controls that match what marketing materials promise.

Fragmented Regulation and Geopolitics

Some of your clients no longer work inside a single AI legal regime. Multinational clients, or companies with diverse operations and vendors must accommodate several different governance systems.

In the European Union, the AI Act relies on a risk-based structure. It bans a narrow group of unacceptable systems and imposes heavy duties on high-risk uses such as employment, credit, health, and critical infrastructure. Lower-risk systems carry transparency obligations rather than full compliance programs.

In the United States, federal action has come through executive orders and agency guidance, now in flux under the new administration, layered over increasingly active states. Export controls for advanced chips and some security requirements remain in place. And in certain sections, additional rules apply.

For a multinational client, the same model may be high-risk in the EU, lightly regulated in some US contexts, and subject to licensing and content rules in China. Decisions about where data sits, which models are used, and which vendors you trust are, in practice, regulatory choices. Lawyers who understand this map can steer multi-national boards toward architectures that keep options open rather than pinning the business to a deployment that works in one region and becomes a liability in another.

Best Practices For Lawyers To Stay Flexible in a Moving War

The goal is not to predict the winner of this massive AI war. And we are not close to the end of the war. To be sure, this war benefits consumers. Frontier models fight to keep their tools on the cutting edge, while keeping consumer prices down. Rather, the goal is to keep your firm and your clients protected while the fighting continues.

Here are six (6) best practices to keep front of mind as you shop for and select AI tools.

1. Choose vendors for exit, not just for entry. When you evaluate an AI platform, consider how you will leave if you must. Ask the following questions:

Will we be able to export prompts, workflows, embeddings, and fine-tuned models in usable formats?

Does the contract guarantee that our data and logs can be retrieved within a defined time?

Is our data siloed?

Is any of our data used to train or fine-tune the AI tool, including usage patterns?

What is the policy on data retention when we end our contract?

What is the policy on data deletion when we end our contract?

A slightly less powerful model with clean exit rights is perhaps a safer bet than a smarter model that traps you.

2. Look for tool-agnostic architecture. Where possible, choose tools built on platforms that can route to more than one model. This provides protection for when the inevitable happens and models are down or a new version rollout frustrates your process.

3. Look for standard or intuitive user interfaces. User interfaces that are highly specialized or difficult to learn and remember will complicate matters and frustrate users if you decide to switch to another AI tool.

4. Keep control over your own processes and information. Keep your knowledge bases, document stores, and evaluation systems separate from any single vendor. That way, a change in model or provider becomes a configuration problem, not a ground-up revision of how your firm works.

5. Govern experimentation instead of banning it. Create a short-list of approved tools, with clear rules on what can be done with client material and who is accountable for reviewing outputs. Require teams to document which models they used when they build new workflows. But then allow controlled experimentation. AI tools only work if they are being used, and being used correctly. Retire tools that don’t deliver, so the firm does not accumulate shadow systems.

6. Reign in Tool Sprawl. Tool Sprawl can sneak up on you as you implement and govern AI tools. In practice it quietly fragments your data, your workflows. It also complicates AI governance and compounds confidentiality worries. The more unofficial tools lawyers use, the harder it becomes to know where client information is going, which models you depend on, and how to unwind those dependencies if a vendor changes course or the law moves.

Protect Yourself and Your Team First

This AI war will not wait for lawyers to get comfortable. Every new tool, every integration, every time someone in your firm pushes for “whatever tool is most advanced at the moment” you move a little closer to one camp or another. If you pick a tool, you cast a vote. If you refuse to pick, you still fuel the war, only without leverage or a plan.

You do not need to know which model will win, and you do not need to find cover and wait until the dust settles. You do need to move smartly through this battlefield, keeping your data safe, your duties of confidentiality, and your team informed. So decide what you are willing to lock in, what must stay portable, and what you will not trade away, no matter how clever the output looks on any given day.

© 2025 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

Agentic AI in Law

Deploying an autonomous AI in your practice isn’t using a tool—it’s appointing an agent, and you’re liable for what it does within its authority.

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.