November 12, 2025

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

Executive Summary

Artificial intelligence tools are already in your practice, whether you know it or not. From Microsoft 365 Copilot auto-completing your emails to Westlaw's AI research features to the new associate or legal assistant slyly using ChatGPT to make their jobs easier. And even if you’re a solo attorney, you’re likely facing opposing counsel’s use of generative AI. There is no question that AI affects your practice. Are you managing that impact deliberately or just reacting to it?

A comprehensive AI policy is a legal necessity. It's a risk management framework that protects you from malpractice exposure, ethics violations, and client relations disasters while letting you leverage AI's efficiency gains safely. This article explains why each policy component matters, what mistakes to avoid, and how to implement governance that works for real law firms.

The Case for an AI Policy

On Monday, October 27, 2025, the oldest currently serving US senator, Chuck Grassley, scolded the U.S. judiciary on the floor of the Senate for the improper use of AI. The juxtaposition of the oldest senator with the newest technology was not lost on me. His speech was prompted by the admission of two different federal district court judges that they had allowed orders out of their chambers that contained AI-created errors.

U.S. District Judge Julien Xavier Neals of New Jersey and U.S. District Judge Henry Wingate of Mississippi both admitted that certain members of their staff used AI to help prepare court orders. Those court orders each contained AI-generated errors. Both judges have taken corrective action. Judge Neals now has a written AI policy. Far be it from me to claim that a written AI policy would have prevented these publicly embarrassing and professionally horrifying mistakes. However, Judge Neals said he has adopted a written AI policy “pending definitive guidance” from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

So, actually, yes, I’m saying a written AI policy would have turned both fiascos into personnel or training issues and kept them from being exceptionally embarrassing judicial errors. If the judges had each implemented an AI policy, we would be bandying around the names of the law intern and law clerk who took the disastrous shortcuts against the judge’s AI policy, and broke the cardinal rule of using AI in law practice: always review your AI output.

Your Common Sense Isn't Enough

Lawyers are intelligent as a group. Generally, we believe—or at least tell ourselves—that we can competently handle most things. So, it comes as no surprise if many lawyers believe they can make decisions about the ethical use of AI. The reasoning seems intuitive: “Don't upload client confidences to ChatGPT, verify all citations, use your common sense.” But this approach fails in practice for three reasons.

The technology moves faster than individual judgment. What’s ‘safe’ potentially changes monthly. AI models change data handling policies. Unanticipated developments change confidentiality policies. Westlaw's AI features evolved from standalone tools to integrated workflows. Without a policy framework, each attorney user is left to independently research whatever tool they choose. Not only is this inefficient and inconsistent, it’s downright foolish, to the point of malpractice.

Harm from AI often isn't obvious until it's too late. Your associate uploads sensitive client information to an unapproved AI tool. The associate’s goal is to provide the best memo possible to you as the partner on the matter, and the associate isn’t mindful about potential harm. There are no immediate discernible consequences. Six months later, during discovery, you receive Request for Admissions and a Request for Production, asking whether you’ve used AI in your legal work, and for everything you’ve uploaded into the AI tool. The judge overrules your motion to quash. Your client's confidential litigation strategy is now in opposing counsel's hands. Your associate used “judgment,” but lacked the technical knowledge to assess data risks.

Ethical duties require more than good intentions and ‘common sense’. Model Rule 1.1 (Competence) now explicitly includes understanding technology's “benefits and risks.” Comment 8 doesn't say “use common sense about AI.” It requires lawyers to “keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.” Saying “I didn't know Grok sends data to third-party servers” isn't a defense—it's evidence of incompetence.

The 5 Failure Modes You're Fighting

AI policies address five (5) categories of risk, each tied to concrete exposure. These are not necessarily listed in order of criticality or importance. Your AI Policy should prevent or at least reduce exposure in each of the five (5) categories.

1. Malpractice Liability & Ethical Violations

Scenario: Your associate uses an AI research tool that generates a non-existent case citation. The cite makes it into a brief, which gets filed in court. The court sanctions you under Rule 11. Your client sues for malpractice, claiming the sanctions and adverse inference damaged their case.

We have the same old duties, but AI is allowing us to breach them in new ways. Bad AI outputs that slip into a filing become Rule 3.3 problems (candor), then Rule 11 problems (sanctions), and finally malpractice problems when the client is unhappy with the result. We’ve already seen the arc in cases like Mata v. Avianca—fabricated citations, judicial rebuke, and costs shifted to counsel—and in certain judges’ standing orders demanding certifications about AI use. An AI policy lowers that risk the boring (and reliable) way: it requires human verification of every quote, cite, and factual assertion in court-facing work; maintains a register of AI-related standing orders and a pre-filing checklist; ties access to training and documented competence under Rule 1.1; and treats configuration, logging, and vendor DPAs as part of safeguarding Rule 1.6 confidentiality. In other words, the policy doesn’t “blame the robot”—it proves the lawyer exercised reasonable care, supervised nonlawyers and vendors, and communicated with the client about methods and fees before the dispute ever arises. That alignment with ABA Formal Opinion 512 (competence, confidentiality, communication, fees) and longstanding cybersecurity guidance (477R) is what turns AI from a sanctions magnet into a defensible tool.

2. Lack of Candor toward the Tribunal

This failure is one we have seen altogether too often, even by large top-tier firms. The harsh truth is that this is toxic to your case and reputationally lethal. AI tools can and will fabricate cases, misquote authority, and smooth over uncertainty with confident nonsense. Hallucinations fall into three (3) categories: 1) answers that are completely wrong, 2) answers that are incomplete, and 3) answers that are plausible but incorrect. The last two are what are tripping up the vast majority of lawyers, judges, and even experts, being sanctioned and publicly embarrassed by their inappropriate AI use. When a hallucination slips through safeguards, the safeguards were insufficient. And when a fake case citation makes it into a filing, it triggers Rule 3.3 duties, sanctions, and client distrust. Courts have already sanctioned lawyers for AI-invented citations. Do not fall into this trap. You can track worldwide AI in legal filings errors here.

A sound policy combats this by (i) making human source-verification non-negotiable for every quotation, citation, and factual assertion in court-facing work; (ii) maintaining a register of AI-related standing orders by jurisdiction with a pre-filing checklist; (iii) requiring the responsible attorney to attest that authorities were pulled from primary sources; and (iv) training lawyers on known failure modes (hallucinations, phantom pin cites, paraphrase drift) so review is targeted and explicit. This puts into practice Model Rule 3.3 and the ABA’s Formal Opinion 512.

3. Confidentiality Breaches and Privilege Loss

The primary harm most attorneys are concerned about with AI use is silent data leakage:

confidential client information (CCI) copied into prompts, logs, or vendor training corpora;

information retained outside your control;

cross-border processing; or

misconfigured tools that later force privilege battles over “disclosed” facts.

An AI policy mitigates these risks by clearly setting expectations and safe boundaries. Your AI Policy must recognize Model Rule 1.6’s duty to safeguard information, the ABA’s 477R guidance to use “reasonable efforts” and enhanced security where risk warrants, and Formal Opinion 512’s reminder that AI use doesn’t relax duties of confidentiality, competence, and reasonable fees.

4. Inadequate Supervision

Scenario: A paralegal uses an unapproved document automation tool that makes substantive errors. You're liable under Rule 5.3 (Supervision of Nonlawyers) because you had no system to track what tools the staff were using.

Law firms need to supervise their AI technology as much as they need to supervise all of their employees’ use of AI. The harm here is twofold: lawyers who don’t understand how AI tools work (or how they’re configured) make bad judgment calls, and firms that don’t supervise staff and vendors let those mistakes escape into client work. That is a straight line to Rule 1.1 problems (competence) and Rules 5.1/5.3 failures (no reasonable firm measures; inadequate oversight of non-lawyers and vendors).

A strong policy converts those duties into standard operating procedures. It defines the minimum skills required for users, assigns a responsible attorney to each matter to review AI-assisted work products, requires documented training before access, and establishes checklists that force lawyers to understand a tool’s capabilities, limitations, configurations, and data handling before using it. It also requires attestations on significant filings, sets escalation paths when outputs look wrong, and makes supervisory accountability explicit (who approves, who reviews, and how deficiencies are corrected). In short, the policy turns “be competent and supervise” from an aspiration into repeatable practice—exactly what Model Rule 1.1 (cmt. 8) and Rules 5.1/5.3 demand, and what ABA Formal Opinion 512 reinforces for AI specifically.

5. Reputational Damage

Clients look to you, their lawyer, to champion their case, protect them from lurking potential harm, and give them thoughtful options. They don’t want in-depth information on your tech stack, but they do want to know that you will not betray their trust. And they aren’t willing to just take your word for it. They want to know that you are competent, what will happen to their data, and what the representation will cost them.

When an attorney at your firm is ‘caught’ with fake citations in filed documents, this reflects badly on the entire firm. Clients lose confidence in the firm’s ability to protect their best interests. Even if their information or case was not in jeopardy, clients still worry, and question whether you are able to manage their case or transaction. The firm will feel some of this reputational damage immediately, but reputational damage is far-reaching. It can be difficult to combat, and even more difficult to rehabilitate.

Affirmative Benefits

Beyond risk mitigation, a well-defined AI policy provides your firm with several strategic advantages.

Competitive differentiation: When a potential client asks, or a corporation’s or agency’s RFPs ask, “What is your AI policy?” you have a ready, substantive answer that’s been in place, and perhaps even updated. Technically sophisticated and unsophisticated clients alike are increasingly expecting firms to use AI, although they have some concerns. And general counsel at regulated companies want to know that their outside firms have thought through AI governance frameworks. Having a well-considered standard AI policy builds confidence and reduces friction for clients to retain you.

Faster tool adoption: Pre-approved tools let attorneys start using vetted technology immediately rather than waiting months for ad hoc reviews. You capture efficiency gains without sacrificing safety. And having a procedure to consider new AI tools, and set timelines to receive answers on whether a new AI tool will be approved, will help curb rogue AI use – called “Shadow AI.”

Better training ROI: Training should not consist of generic “Rah-rah AI” seminars—it should focus on specific workflows, and hands on training. For example, “Here's how to use Westlaw AI while complying with our source-checking mandate” or “Here are the acceptable uses of MS Word’s Copilot.” When legal professionals know how to use AI tools, they are far more likely to use them appropriately.

Clearer billing practices: Your policy should resolve the question of “how does your AI use affect your billing” before it becomes an angry conversation or fee dispute. Clients appreciate transparency more than they resent the use of AI.

Incident preparedness: Having an incident response system or set of procedures means you're not inventing crisis response during an actual crisis. You know exactly when to notify clients, when to escalate internally, and when to just log and learn from mistakes.

Best Practices for Successful Implementation

You need an AI policy in order to avoid pitfalls and protect your firm’s greatest asset – its reputation. But there is a best way to go about it in order to make it as pain-free and frictionless as possible. Here are strategies that make AI policies effective:

1. Start with Pre-Approved Tools

Don't boil the ocean. At or before implementing the full policy, identify 2-5 AI tools you'll use. Easy choices often include:

Microsoft 365 Copilot (if you have E3/E5 licenses)

Westlaw AI or Lexis+ (whichever is your primary research platform)

Maybe one e-discovery/document review tool

Verify the configurations of those tools, document them in your AI policy and authorize their immediate use. This gives attorneys approved tools from Day 1. They're not secretly using unapproved AI tools while they wait months for approvals. Instead, they can start using approved tools and gain confidence in the tools’ efficiency gains. Then implement an approval process for new tools. The approval process should be clear, understandable, and predictable. This disincentivizes unauthorized uses and shadow use.

2. Champions, Not Mandates

Identify one or more “AI champions” in the firm—attorneys who are enthusiastic about AI and willing to share their best uses, successes, and difficulties. These will likely be senior associates. Give them slightly more latitude (faster approval for pilot tools, first access to new capabilities) in exchange for evangelizing to peers.

When skeptical attorneys see champions achieving good results, they become interested. Bottom-up adoption is more sustainable than top-down mandate. It is the best, fastest, easiest way to change the culture at your firm.

The bonus is that champions also provide feedback: “This logging requirement is too burdensome” or “We need better training on verification workflows.” They make your AI Policy a living, useful document by helping to refine it based on real-world use.

3. Client Communication

Standardize what lawyers and other staff say when a client asks about their use of AI. You might even provide scripts:

Proactive disclosure (engagement letter): “Our engagement letter mentions that we use AI tools for research and drafting. These are vetted enterprise tools with strong confidentiality protections—Westlaw AI, Microsoft 365. All AI-assisted work is reviewed by responsible attorneys. Let us know if there is anything specific you'd like to know about our AI use.”

Explicitly state your safeguards: “We have a comprehensive AI policy. We only use approved enterprise tools with contractual data protections and never use consumer tools like ChatGPT. Qualified attorneys review all AI outputs, and court filings undergo mandatory verification. We can provide more detail on any aspect. If you have specific concerns or restrictions, please let us know.

Address client preferences for AI restriction: If you are confident in your AI use and the ROI, you can have candid conversations with your clients who say, “We don't want any AI used on our matters.” For example, you could respond, “We can discuss that. Some AI is embedded in standard tools, such as Microsoft Word's editor and Westlaw's research platform. Avoiding all AI might not be practical. Let’s discuss what specific risks concern you. We might be able to address those through targeted restrictions rather than complete prohibition.”

If the client still insists on no AI, you should consider whether this decision increases the cost of their representation by more than 20% or delays it by more than 30 days. If yes, discuss whether you need to adjust the scope or pricing. Prepare client-facing staff and attorneys for these client concerns.

There are some issues that deserve extra consideration. For example, if your AI sends information to a vendor, crosses borders, meaningfully changes how the work is done, or alters the cost of representation, that’s part of the “means of representation” (Rule 1.4) and should be explained up front. Ideally, they should not only be part of your engagement letter, but also a discussion between you and your client.

4. Celebrate The Wins

Take time to share best practices, good catches, and the most effective uses of AI in your firm. When an attorney or assistant catches an AI error before it causes harm, acknowledge it. When AI genuinely saves time/improves quality, be sure to praise the attorney/s using it, and consider sending firm updates. For example, “Partner Y reports the new document review AI reduced discovery costs 30% on Matter Z.” This will help change the culture at your firm to one of responsible AI use with verifiable ROI.

5. Make Compliance Easy

Reduce as much friction as possible in your team’s adoption of the AI policy. Don't make decisions on new AI tools equivalent to getting an act through Congress. To the extent possible, integrate your policy with existing workflows so that potential errors don’t sneak past your firm and make it into filed documents.

Going From Policy to Practice

Feel free to use the AI policy template provided by Lexara. Modify it and adjust it to fit your firm and your intentions. But keep in mind, templates only work if you implement them thoughtfully. It’s fine to allow the firm and all the AI users a chance to ease into the policy. Within a few weeks, however, you should have established a functioning AI governance framework, including clear rules, approved tools, trained personnel, incident response capabilities, and an improvement process. That way, you're managing AI risk deliberately rather than reactively.

If you need additional information, consider consulting your jurisdiction's bar ethics hotline, or legal technology consultants with AI governance expertise.

© 2025 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

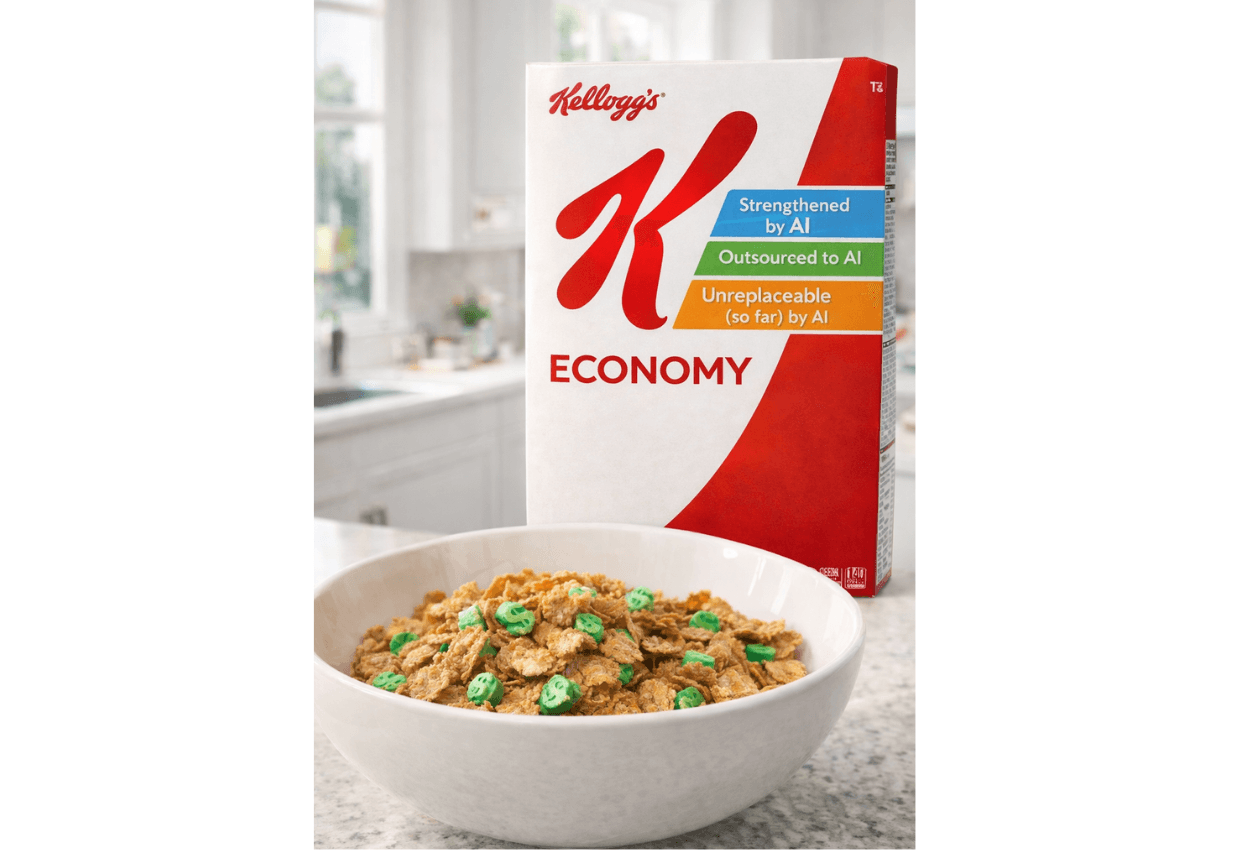

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.

Legal Fees Aren’t Going Down Despite AI Adoption in Law

AI has made BigLaw faster and more profitable—but not cheaper. Instead of expanding access to justice, efficiency gains are flowing upward, leaving legal costs high and the justice gap intact.