December 17, 2025

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

Image by Joyce N. Boghosian, used pursuant to 17 U.S.C. §§ 105, 106 (2020)

Executive Summary

President Trump’s December 11, 2025 AI Executive Order seeks national uniformity in AI regulation to keep the United States innovative and dominant in AI. He explicitly links this dominance to economic and national security. And so he took aim at divergent state laws, seeking to corral them with threats of court challenges, and denial of federal funding. But will it clear the way for innovation, as he hopes? Or will it lead instead to greater instability? The AI Executive Order is likely to prolong uncertainty for AI businesses, undermining innovation rather than delivering the uniform national AI framework hoped for.

On December 11, 2025 President Donald Trump signed his AI Executive Order “Ensuring a National Policy Framework for Artificial Intelligence.”

That day I posted the top 5 things lawyers needed to know about the new AI EO. I thought I would leave it at that, but find I can’t. While not wanting to make this newsletter overly political, I do want to include important information on AI in law for legal professionals, which, in this case, involves politics.

Trump’s most recent AI executive order is an unfortunate use of executive power because it seeks nationwide uniformity not through Congress and durable legislation, but through an executive-branch strategy of federal pressure and litigation against states that have adopted differing rules. Whatever one’s preferred end state for AI innovation and governance, this approach predictably intensifies state–federal conflict and invites years of uncertainty about which rules apply, when, and to whom—exactly the environment that undermines responsible stable compliance for the public and for businesses building or deploying AI. Rather than paving the way for innovation, it has a chilling effect on AI innovation.

Two Ways to Achieve Uniformity

President Trump’s stated objective in this Executive Order is to achieve regulatory uniformity in regard to AI. There are at least two ways to do that. Ok, there are a large number of ways to achieve uniformity – far more than two. But I’m referring to two that are somewhat synonymous.

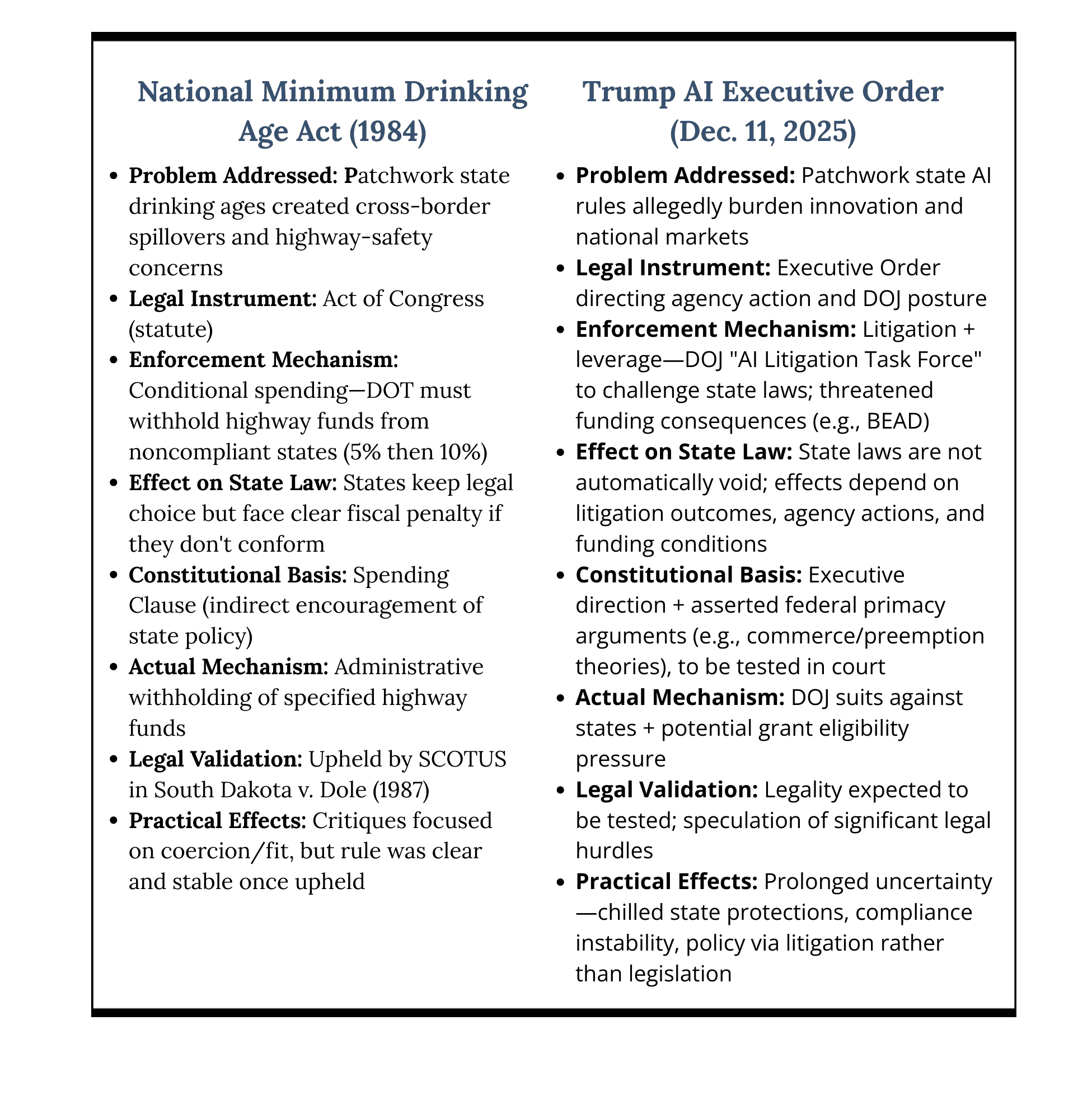

There is a meaningful difference between national uniformity achieved through legislation and “national uniformity” pursued through an executive directive aimed at challenging state policymaking. The minimum drinking age offers a useful comparison because it shows how the federal government has historically responded to a state-by-state patchwork using tools that are at least structurally transparent and democratically accountable—namely, a statute and a clear incentive mechanism—rather than a broad, litigation-forward campaign to deter state experimentation. That contrast helps clarify what is unusual (and potentially risky) about the AI executive order’s approach.

First Approach – Congress Passes a Law

In 1988, Wyoming became the last state to finally agree to raise the age that one could legally purchase and consume alcohol. Before that time, states had legal drinking ages as low as 18 years old. Congress and state officials argued varying ages created predictable cross-border spillovers—young people could legally drink in a nearby lower-age state and then drive home, increasing the risk of accidents on the highways. Rather than “preempt” state alcohol laws outright, Congress enacted the National Minimum Drinking Age Act (23 U.S.C. § 158) July 17, 1984, using a ‘federalism compromise.’ It conditioned certain federal highway funds on states making it unlawful for people under 21 to purchase or publicly possess alcohol (with a phased funding penalty—5% initially, 10% thereafter—for noncompliance).

This resulted in a relatively transparent, democratically accountable route to national uniformity. Congress legislated, spelling out the conditions. They tied it to a federal spending program. And with the courts as the final arbiter, the approach was tested and upheld in South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987).

Second Approach – Executive Order Issued by One Man

Trump’s AI Executive Order pursues uniformity primarily through executive-branch litigation, and funding pressure, which can generate broad uncertainty and collateral consequences while the courts and agencies sort out the limits of executive authority.

The Executive Order of December 11, 2025 was expressly signed to accomplish three purposes:

Stop states from overly restraining AI innovation.

Allow the U.S. to maintain AI dominance, as an economic and national security imperative.

Root out state AI laws that allegedly require compelled speech and “truth-altering” outputs.

Let’s use the drinking age law to compare and contrast with the AI Executive Order of December 11.

The problem in both cases was a patchwork of state laws. The goal in both cases was national uniformity. The enforcement mechanism is whether the parallels end. In the Drinking Age solution, the goal was clear and agreed upon by Congress. The enforcement was likewise clear: states could maintain a lower drinking age (as Wyoming did in order to gain an economic boost from a greater section of the population being able to legally purchase alcohol), but in so doing would face clear consequences. States knew how much federal funding they would lose if they refused to raise drinking age limits.

The AI Order, on the other hand, is much more mysterious and convoluted. No one is entirely certain what the consequences of refusing to modify or revoke laws. As I used to tell my clients, litigation is wildly unpredictable. Strong cases can lose, and weak cases can win—because outcomes often turn on uncertain factors like which judge you draw and how they interpret the law. You can reduce risk, but you can’t control the outcome.

For these reasons, the AI Order is likely to create more confusion, uncertainty, and waiting in limbo to find out how things eventually shake out. And although the AI Order says the President needs to work with Congress to achieve regulatory uniformity, that mention is the only thing about this Order that involves Congress.

This Is Not a Novel Approach

Trump is hardly the first president to use an executive order to get what he could not or did not want to wait for in Congress. Many a president have used their executive power to accomplish their various goals.

In Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), the Supreme Court held that President Truman’s executive order directing the federal government to seize and operate steel mills during the Korean War was unlawful because the President may not take such domestic action unless it is grounded in the Constitution or authorized by Congress; the Court rejected the idea that “inherent” executive power could substitute for statutory authority in that context. Justice Jackson’s concurrence (the enduring takeaway) frames presidential power on a spectrum: it is strongest when acting with Congress, uncertain when Congress is silent, and at its “lowest ebb” when the President acts contrary to Congress’s expressed or implied will.

That framework is a useful lens for the December 11, 2025 AI Executive Order, which directs the Department Of Justice to create an “AI Litigation Task Force” to challenge state AI laws as unlawful (including as unconstitutional regulation of interstate commerce or “preempted” by federal law), and also contemplates identifying state laws for potential federal grant-funding consequences.

The key contrast is that Truman’s order directly displaced private control of property immediately, whereas Trump’s order primarily reorients federal enforcement and litigation posture (and leverages funding), leaving actual invalidation of state laws to courts—but Youngstown still matters because any claimed “override” of state law generally must rest on valid federal authority (statute/authorized regulation, or a clear constitutional power), not executive preference alone.

This most recent AI executive order is an unfortunate use of executive power because it seeks nationwide uniformity not through Congress and durable legislation, but through an executive-branch strategy of federal pressure and litigation against states that have adopted differing rules. Whatever one’s preferred end state for AI governance, this approach predictably intensifies state–federal conflict and invites years of uncertainty about which rules apply, when, and to whom—exactly the environment that undermines responsible regulation and stable compliance for the public and for businesses building or deploying AI.

Is The December 11 Executive Order Federal Preemption?

Section 7 of the AI Executive Order is titled “Preemption of State Laws Mandating Deceptive Conduct in AI Models.” Which leads to the question, is this really preemption, in the ‘term of art’ sense of the word?

Federal preemption is found in the Supremacy Clause, Article VI, Clause 2, of the U.S. Constitution. Simply stated it’s the doctrine that valid federal law can displace conflicting state law—most commonly through (1) an Act of Congress that expressly preempts state regulation, or (2) conflict/field preemption where a state rule cannot coexist with federal requirements. Preemption can also come from federal regulations when an agency is acting within delegated statutory authority—the Supreme Court has been explicit that federal regulations can have “no less pre-emptive effect than federal statutes.” Fidelity Federal Savings and Loan Ass’n, et al v. Cuesta, 458 U.S. 141 (1982)

An executive order, by contrast, typically binds federal agencies, not the states. It can pressure states by directing federal agencies, setting federal priorities, and conditioning federal funding on compliance. It usually does not “wipe out” state statutes on its own.

What Federal Preemption Looks Like

As a very surface-level reminder from 1L Con Law, federal preemption can be either express or implied. Express, when the language of the law states the superiority of the federal law. Implied, when the effect of the law results in a conflict between the federal and state laws, and the federal law wins out.

An example of Express Preemption:

Airline Deregulation Act (1978) — Congress expressly barred states from enforcing laws “related to a price, route, or service” of air carriers (49 U.S.C. § 41713).

CAN-SPAM Act (2003) — Congress created a national baseline for commercial email and expressly preempted many state commercial email statutes (with an exception for state fraud/deception laws in 15 U.S.C. § 7707) (15 U.S.C. Chap. 103)

An example of Implied Preemption:

Hines v. Davidowitz (1941) — The Supreme Court held that Pennsylvania’s alien-registration law was preempted because it conflicted with, and stood as an obstacle to, the federal alien-registration system (an example of implied conflict/obstacle preemption).

What “States Yield” Looks Like (Enforcement, Not Preemption)

Executive orders allow the president of the United States to act alone, contrary to what we are taught in school as the system of “checks and balances.” Executive orders have been used numerous times, by numerous presidents. They have been used to create federal parks, resolve labor disputes, and at times, even to force states into a position of yielding to presidential will. President F.D. Roosevelt issued by far the most, although in fairness he served during WWII, and spent the longest time in office of any U.S. President.

A few notable examples:

Eisenhower — Executive Order 10730 (Sept. 24, 1957): authorized the Secretary of Defense to take steps to enforce federal court orders in Arkansas regarding Little Rock school desegregation and to remove “obstruction of justice,” including use of federal forces—functionally overriding Arkansas’s resistance to integration.

Kennedy — Executive Order 11053 (Sept. 30, 1962): directed Department of Defense to enforce federal court orders and remove “obstructions of justice” in Mississippi relating to the University of Mississippi integration crisis, authorizing use of federalized Guard/armed forces. See also American Presidency Project.

Kennedy — Executive Order 11111 (June 11, 1963): authorized federalization of the Alabama National Guard to enforce desegregation orders during the “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” at the University of Alabama. See also American Presidency Project.

In limited foreign-affairs contexts, the Supreme Court has found state laws displaced where they conflict with the federal government’s foreign policy implemented through executive action were legal (e.g., American Ins. Ass’n v. Garamendi).

The AI EO expressly directs the Department of Justice to form an AI Litigation Task Force to challenge state AI laws—including arguing they regulate interstate commerce, are preempted by existing federal regulations, or are otherwise unlawful. But this is surely a misnomer because the plain language of the December 11 AI order does not purport to override US state laws. Rather, it sets out a task force to litigate state AI laws, and perhaps deny broadband funding. It is therefore best described as a litigation-and-leverage strategy (challenge state laws; argue conflict; use federal funding), rather than preemption in the classic “Congress has spoken” sense.

Will A Litigation-and-Leverage Strategy Accomplish Trump’s Goals?

Trump’s express goal is to free-up AI companies to innovate, unfettered by a patchwork of state laws, thus keeping the US dominate in AI power. Rather than wade through the complications and delay of urging Congress to pass a uniform law, he’s chosen a route that he must believe will fast track his objective. But his litigation-and-leverage strategy can backfire in at least two ways.

First, it can chill legitimate state protections—including transparency, consumer protection, anti-discrimination, and competition-focused measures—because states and regulated entities may pause, narrow, or abandon rules in anticipation of federal challenge. That creates a practical “regulatory freeze” precisely where states are acting as first responders to emerging harms, even while Congress has not yet enacted a comprehensive national framework.

Second, the strategy can increase—not decrease—regulatory uncertainty. When the executive branch signals that a wide range of state AI laws are targets, the result is often a prolonged period of piecemeal injunctions, inconsistent court rulings, and shifting enforcement priorities. Businesses face unstable compliance obligations; consumers face uneven protection; and policymakers are pushed into a waiting game. In other words, an order designed to avoid a “patchwork” can unintentionally produce a different—and often worse—patchwork: one driven by litigation outcomes and administrative discretion rather than clear, predictable rules.

For example, consider Illinois’s Artificial Intelligence Video Interview Act (820 ILCS 42), which has been in effect since January 1, 2020. It requires employers using AI to analyze recorded video interviews for Illinois-based positions to (1) notify applicants that AI may be used, (2) provide information explaining how the AI works and the general characteristics it considers, (3) obtain the applicant’s consent before using AI, and (4) limit sharing of interview videos and delete them upon request. It also includes a demographic reporting requirement in certain circumstances, requiring employers that rely solely on AI analysis to determine who gets an in-person interview to collect and report specified race/ethnicity data.

Now layer on this AI Executive Order, which directs the DOJ to form an “AI Litigation Task Force” whose “sole responsibility” is to challenge state AI laws the Administration deems inconsistent with federal policy, including on grounds they are unconstitutional, preempted, or otherwise unlawful, and it directs Commerce to identify state laws that may compel disclosures/reporting in potentially unconstitutional ways. Regardless of who ultimately prevails, the practical consequence for multi-state employers is immediate uncertainty. Should they invest in (or maintain) Illinois-specific disclosures, consent workflows, vendor contracts, retention/deletion processes, and demographic reporting pipelines? Or would they be better off to pause or scale back in anticipation of litigation, injunctions, or shifting federal enforcement priorities?

The fallout in terms of state-based funds that will need to go to defending litigation, and the federal funds that will go into bringing these suits is disheartening, to say the least. How many other, more productive, beneficial uses could this soon-to-be-vast amount of money be put toward? Here are a few off the top of my head: housing those in need, food for people who have food insecurity, retraining for people who are likely to be displaced by AI advancements, and educational excellence.

In other words, the result is not the end of a patchwork, but a new patchwork—one defined by court orders, agency positions, and compliance whiplash rather than stable, predictable rules.

Perhaps AI companies will consider the December 11 AI EO to be carte blanche for them to innovate in any way they see fit. That raises other problems. For example, Trump is in his second term. When the next president takes office, there is a good possibility that this AI EO will be reversed, much like Trump did to Biden’s two (2) AI EOs. Companies are aware of this and may take a more cautious approach than they otherwise would have, knowing this policy likely won’t last forever. The bottom line is more uncertainty.

The December 11, 2025 AI EO Won’t Bring The Uniformity It Hopes For

In the end, the strongest critique of this Executive Order is not that it prefers national uniformity over state experimentation—reasonable people can disagree on that policy choice. Personally I have been calling for a federal AI law for many months.

My concern here is the means. A “litigation-and-leverage” approach is a blunt instrument for a domain as broad and fast-moving as AI, and it risks substituting executive discretion for the deliberative, durable rulemaking that Congress is designed to produce. Instead of resolving the very “patchwork” it decries, the Order may create a worse one, as we wait for the injunctions, legal decisions, agency interpretations, and compliance reversals that leaves businesses guessing, consumers unevenly protected, and state policymakers stalled in a waiting game.

If the goal is a coherent national AI framework, the better path is the initially more difficult one. Congress should debate and enact an AI framework, agencies should implement it through transparent processes within clear statutory bounds, and courts should remain the backstop—not the primary engine—of AI governance.

© 2025 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.

Legal Fees Aren’t Going Down Despite AI Adoption in Law

AI has made BigLaw faster and more profitable—but not cheaper. Instead of expanding access to justice, efficiency gains are flowing upward, leaving legal costs high and the justice gap intact.