February 12, 2026

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

3 Biggest Takeaways:

per-seat licensing for our legal subscriptions is under some serious structural pressure,

commoditized legal work is increasingly automatable, and

AI’s mere existence might cause you to have to defend your fees.

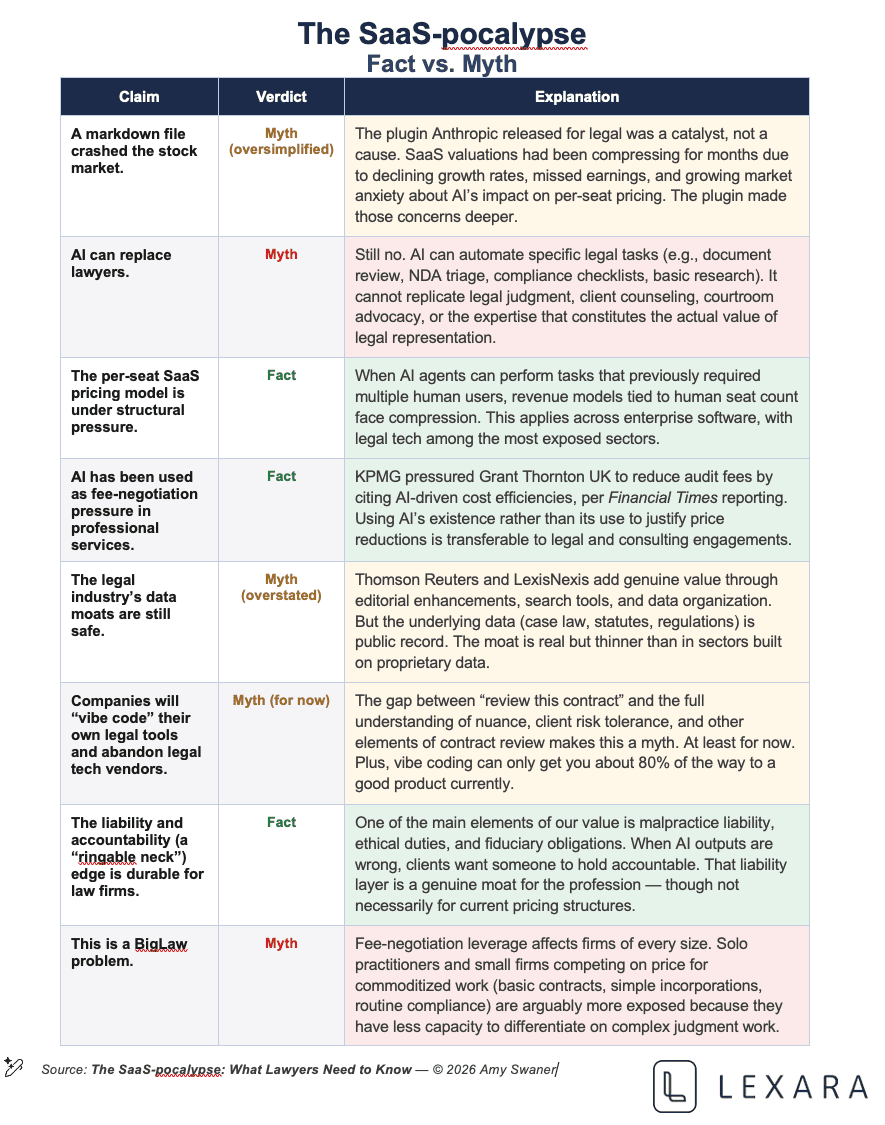

What Happened -- the SaaS-pocalypse

On January 30, 2026, Anthropic — the company behind the Claude AI model — released a set of open-source plugins for its desktop AI tool, Claude Cowork. One of them handles legal contract review. It can triage NDAs, flag nonstandard clauses against a negotiation playbook, and generate compliance summaries.

The plugin is open source meaning anyone can read, modify, or use the source code that created it. When people read it, they found roughly 200 lines of structured markdown (eg a table). It’s essentially first-year law school concepts organized with workflow logic and a prompt structure. It’s got a disclaimer that all output should be reviewed by licensed attorneys. Which all attorneys should know by now, but we still keep seeing problems.

Within 48 hours, the market responded:

Thomson Reuters posted its largest single-day stock decline on record, falling approximately 16%.

Private equity firms with heavy professional-services exposure -- Ares Management, KKR, TPG and Blue Owl — each fell around 10%.

In aggregate, the sell-off erased an estimated $285 billion in market capitalization. Financial media quickly branded it the “di-SaaS-ter”, and the “SaaS-pocalypse.” See eg, The Street, Yahoo!Finance, and Inc.

Why An Open Source File Is Causing So Much Chaos

The plugin itself didn’t justify that reaction. Any competent prompt engineer-- or, candidly, any tech-literate lawyer with a weekend to spare--could assemble something functionally similar. The market wasn’t reacting to the plugin. It was reacting to what the plugin made possible.

The entire enterprise software economy, from Salesforce to Thomson Reuters, is built on per-seat licensing: every human who touches the tool pays a license fee. That model works when humans are the bottleneck. Each human needs their own login. But it breaks when an AI agent can perform the work of multiple humans without requiring multiple logins.

If one AI agent can do the legal research that previously required ten paralegals with ten separate Westlaw subscriptions, Thomson Reuters’ case law database doesn’t lose any of it value. But it loses nine seats of revenue. Ironically the data becomes more important in an AI-driven world -- it’s the fuel the agents run on. But the per-seat pricing model that monetizes that data is structurally unsound.

The market had been quietly signaling this for months. Software-sector forward price-to-earnings ratios had been compressing. Companies were missing revenue estimates at rates not seen since the post-COVID correction.

More AI Doesn’t Mean Less Software

NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang offered the strongest counterargument at the Cisco AI Summit shortly before the sell-off. His position is essentially this:

AI doesn’t replace software; AI runs on software.

More AI agents means more databases, more APIs, more middleware.

Every agent that replaces a paralegal still needs Westlaw’s data, a CRM, and document management.

AI should increase total software demand.

Which makes sense. Huang isn’t wrong, but he’s not making the persuasive case he thinks he is. Nobody serious contends that the world needs less software. The contention is that the world no longer needs to pay for software the way it currently pays for software. Huang is defending the product. The market is attacking the pricing model. Those are different things, and confusing them could be how SaaS giants lose their edge.

Consider the newspaper analogy we so often turn to when trying to explain the impact of AI. It’s not perfect here, but it is instructive. Print media had content people wanted -- local reporting, investigative journalism, weather. The internet didn’t make that content worthless. It destroyed the access model, and to some extent, the pricing model. You no longer had to buy an entire newspaper to get the one section you cared about and that advertisers would pay premium rates to reach readers with no alternative. The content survived. The business model didn’t.

The Market Sell-Off Explained By An Accounting Firm

While the market was fixated on Thomson Reuters’ share price, a quieter story broke that received far less attention. But it tells us so much more about where we’re headed.

KPMG, one of the Big Four accounting firms, pressured Grant Thornton UK, its own auditor, to cut audit fees. KMPG’s rationale was that AI reduces the cost of performing audit work, and those savings should flow to the client. Grant Thornton initially resisted, arguing that high-quality audits require expert human judgment and that fees reflect the cost of the workers (a/k/a the humans). KPMG’s response, per the Financial Times, was lower your prices, or we’ll find a new auditor. Grant Thornton lost this game of chicken, and the fees dropped approximately 16%.

This matters more than any stock chart because it’s an operating event, not a market event. A real company used AI’s existence -- not its use, not its deployment, but its very existence -- as leverage in a real fee negotiation to extract a real price concession.

How long before other legal clients follow suit?

Why Legal Is Ground Zero

The legal profession is more exposed to this dynamic than almost any other knowledge-work sector, for three compounding reasons.

The data moat is thinner than it looks. Thomson Reuters and LexisNexis have operated what amounts to a duopoly on legal research for decades – ever since I’ve been practicing law. But unlike Salesforce’s proprietary customer data or SAP’s enterprise resource planning logic, the underlying data in legal research -- case law, statutes, regulations -- is public record. That’s right. These companies are monetizing public information. They add proprietary organization, search functionality, and editorial enhancements. Their organizational model alone has survived lawsuits. That’s a real value-add, but it’s a weaker moat than proprietary data. An AI agent that can efficiently search, synthesize, and cite public legal sources puts direct pressure on the premium these platforms command.

Commoditized legal work is immediately vulnerable. NDA review, due diligence document review, regulatory compliance checklists, standard contract drafting, discovery review; these are high-volume, pattern-recognizable tasks that AI handles competently today. They also represent a significant share of associate and paralegal billable hours at many firms. The Anthropic plugin demonstrated, in 200 lines of open source code, that basic contract review doesn’t require a Westlaw subscription or a first-year associate. It requires structured prompts and a competent model.

The fee-negotiation pressure is already here. Corporate legal departments and procurement teams don’t need to be actively using AI to use it as a lever. They need only point to its existence. Then they pattern their conversation on KPMG’s conversation. It’s pretty straightforward: “So, we know AI can perform first-pass contract review, document summarization, and basic legal research. Your staffing model assumes associates and paralegals doing that work at hourly rates. Justify your rates.” If it isn’t happening in your practice yet, it almost certain will be.

What This Does Not Mean

Make no mistake -- this is not a story about lawyers being replaced. AI never has been that story. It is a story about how legal services are priced and delivered.

The gap between what a client asks for and the full universe of knowledge needed to do it well is acute in legal work. A client saying “review this contract” provides perhaps just a small fraction of the information a lawyer needs to accomplish the task. Risk tolerance, deal context, jurisdictional nuances, relationship dynamics, business objectives. That implicit knowledge is the actual value a skilled lawyer provides, and no markdown file can replicate it.

The accountability edge is equally durable. Legal is a regulated profession with malpractice liability, ethical duties, fiduciary obligations, and bar oversight. When an AI hallucinates a case citation as happened in Mata v. Avianca, someone is liable. Enterprises need a “ringable neck,” someone who can be accountable when something goes wrong at 2:00 a.m. before a filing deadline. Preferably someone with a generous E & O carrier. That accountability layer becomes more valuable as AI-driven workflows grow more complex, not less. Which is not at all comforting for lawyers, that one of our value-adds is to serve as a backstop for accountability when something goes wrong.

But this does expose a huge problem with the billable hour pricing model, and the assumption that legal work scales linearly with the number of humans billing hours against it.

What You Should Be Thinking About

If you’re in private practice

The firms that will thrive are those rethinking what work gets done, by whom, at what price point, and with what technology -- not those running the same staffing model with a chatbot added in for good measure.

You’ve got some time, but you should be thinking about it to get ahead of the pressure. You need to be able to defend your pricing when clients use AI’s existence as leverage. And that’s true whether or not you are using AI in your practice, as we saw in the KPMG example, above.

If You’re In-House

You now have a credible basis to renegotiate outside counsel rates on any work that is high-volume and pattern-recognizable. You also have an obligation to understand the ethical and competence implications of AI tools your teams may already be using.

If You’re Advising Clients on AI Strategy

The SaaS-pocalypse is a case study in the difference between product disruption and pricing-model disruption. Your clients’ software vendors-- not just legal tech, but across their enterprise stack--are all facing variants of the same question. That’s an advisory opportunity.

Regardless of Your Role

The ethical obligations haven’t caught up. Model Rules 1.1 (competence), 1.6 (confidentiality), and 5.3 (supervision of nonlawyer assistants) all have direct implications for AI use. State bars are issuing guidance at varying speeds. Unauthorized practice of law questions around AI-generated legal analysis remain largely unresolved. And are generally overshadowed by the hallucinated legal citations that still show up altogether too frequently. This regulatory uncertainty is both a risk and, for lawyers positioned to advise on it, an opportunity.

The Bottom Line

The three biggest takeaways from this moment are first, the "per-seat" licensing for our legal subscriptions is under some serious structural pressure. Second, commoditized legal work is increasingly automatable. And third, AI’s mere existence shifts fee-negotiation dynamics. Even if you’re still not using it in your practice. This dynamics shift won’t hit you tomorrow when you walk into your office. Or even when you send bills out at the end of the month. But start considering your strategy now so you are prepared to answer questions about your fees.

More Like This

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.

Legal Fees Aren’t Going Down Despite AI Adoption in Law

AI has made BigLaw faster and more profitable—but not cheaper. Instead of expanding access to justice, efficiency gains are flowing upward, leaving legal costs high and the justice gap intact.