February 12, 2026

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

Many lawyers now use AI for research, contract review, discovery, drafting, and due diligence while operating with zero understanding of the architecture determining whether those tools work. And lawyers who find no value in AI tools. We’ve confused knowing how to use an interface—prompt engineering--with understanding the technology producing outputs. Understanding context engineering won’t let you fix bad tools. But it will let you recognize bad tools before you stake your professional reputation on them.

Prompt Engineering vs. Context Engineering

Prompt engineering is the question you type into an AI tool’s chat interface. Prompt engineering is important and goes a long way to high quality output.

Context engineering is made up of a number of other factors that also determine how your AI tool responds. Using a legal analogy, prompt engineering is like writing the argument section of your brief. Context engineering is assembling the entire record.

Imagine you are preparing for oral argument. You select which exhibits to use, decide which expert testimony to proffer, highlight portions of depositions, and prepare your bench memo. If you want to win, you don’t select random case citations, leave out expert testimony, and bury your best piece of evidence. You wouldn’t cite cases without checking whether they truly support your proposition. Ok, well most of us wouldn’t.

AI tools work the same way, just with a different decision-maker. The model is your fact-finder / judge. Your prompt is your argument. Context is everything else you’re providing to help the judge reach the right conclusion. Even a perfect prompt can’t save bad context engineering every time.

The difference between your law practice in this analogy and your AI tool is visibility. In litigation, you see your entire record. You made the choices about what to include and how to structure it. With AI tools, a great deal of context engineering happens invisibly in the background. The interface shows you a simple text box for your prompt and a response. You don’t see the retrieval ranking, the document chunking, the example selection, the system constraints—all the machinery operating behind the scenes, all impacting what you get back.

That invisibility creates the illusion that prompts are all that matter. We see the prompts because we write the prompts. But other factors are at play; some you can control, many you cannot. One of those factors is the context window.

A Context Window

A context window is the total amount of text—measured in units called tokens—that an AI model can process and consider at any one time. Everything outside that window is invisible to the model, regardless of its relevance or importance. Context windows have expanded dramatically in the three years AI tools have been popularly available and are still moving fast. Here's where things stand as of early 2026, for consumer tools:

Claude currently offers 200,000 tokens standard, with 1 million tokens available in beta.

ChatGPT-5 features 400,000 input tokens with a 128,000 output window.

Google's Gemini 2.5 Pro and Flash both support a 1 million-token window.

Meta's Llama 4 Scout features a 10 million token context window.

For reference on what those numbers mean, 128,000 tokens is roughly the length of a 250-page book. A million tokens is several thousand pages. A typical 200-page buy-sell agreement sits around 100,000 tokens.

Think of a context window as the desk space available to a very fast, very capable law clerk. Everything on that desk—your contract, the relevant precedents, your instructions, the firm's drafting guidelines—is what the clerk can actually work with at any given moment. Anything that doesn't fit on the desk simply doesn't exist for that clerk, no matter how critical it might be. A 200-page credit agreement, a stack of precedent memos, and your detailed instructions might collectively exceed the desk space available, which means something gets left in the hallway. Context engineering is, at its core, the discipline of deciding what stays on the desk and what doesn't—and for legal work, that decision determines a great deal.

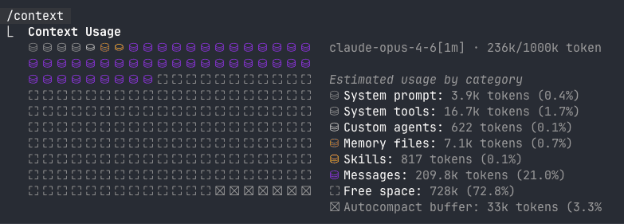

______________________________________________________

Above is a visual representation of a context window for a Claude Code session, with a context window of 1,000,000 tokens. The small squares on the left plus the round icons above them are a visual representation of a context window. The purple icons are token blocks, representing how many tokens have been used out of the context window. You can tell from the legend on the right that some tokens are used up by the system prompt (set by the AI tool creator / engineers). Some of the context window is used by skills, system tools, and in this specific case, custom agents. All of these together are part of a context window.

As the user you are limited to the purple icons and squares as your ‘workspace.’ This looks vast, but the AI tools you are using have significantly smaller context windows.

Context Engineering, In Legal Scenarios

Context engineering is the systematic design of all inputs provided to LLMs beyond your immediate question. It includes how information gets selected for the model to consider, how that information gets structured and chunked, what examples shape the model’s behavior, what constraints define its role and scope, and how limited processing capacity gets allocated across competing needs. I won’t go into the technical components such as retrieval system design, ranking algorithms, etc. because I can feel your eyes starting to glaze over. The conceptual core is simpler recognizing that the model’s entire input environment determines output quality at least as much as the model’s underlying capability.

Think about asking an AI tool to analyze a 200-page credit agreement for indemnification issues. You type “identify indemnification problems” and upload the file. Simple enough. But “something” has to decide which parts of that agreement the model actually processes, in what order, with what surrounding context.

Section 8.3 might reference “limitations in Section 12.5.” Does the model see both sections together, or does the chunking algorithm sever that relationship? Are your firm’s precedent indemnification provisions included for comparison? Does the system know Iowa law governs, or is it applying generic commercial standards? When the context window fills up, does critical material get truncated while boilerplate remains?

Those are context engineering decisions. They happen whether you and I and every other lawyer using AI tools thinks about them deliberately or not. The only variable is whether they’re made well or made badly, intentionally or accidentally.

For contract review, part of context engineering is the chunking strategy. Chunking is the process of breaking large documents into smaller sections that an AI model can process. The boundaries where those breaks occur matter enormously—a provision severed from the cross-reference it depends on is like a contract missing its exhibits. Good chunking preserves the architecture of legal documents (section headers, definitions, cross-references) while bad chunking treats text like a word processor cutting pages at arbitrary margins.

For legal research, context engineering determines whether state Supreme Court decisions rank ahead of out-of-state dicta. Whether recent cases surface first when doctrine is evolving. Whether the model gets enough factual context to distinguish truly analogous precedent from superficially similar but irrelevant decisions.

For due diligence, context engineering determines whether retrieval prioritizes smoking-gun documents over background noise. Whether the system understands hierarchical relationships between disclosure schedules and main agreements. Whether client risk parameters get incorporated without compromising confidentiality.

Same model, different context engineering, radically different results.

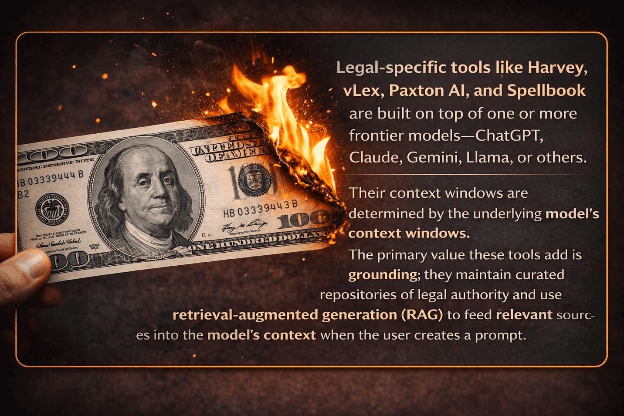

The funny thing about the image of the burning $100 and the words next to it is that it’s a prime example of context windows and how important it is to control them to the extent possible. I went to ChatGPT to have it create a quote for this article, using the wording I pasted in. I did not ask for the burning money. Because the image was in my context window, ChatGPT used it to create the above graphic. Here is the chat that led to this image:

I didn’t mention the burning money when I asked for an image for the quote. But when I said I need. “this” ChatGPT conflated the instructions with what was already in this chat’s context window. An inadvertent, but useful, example of context with AI tools. The lessons are to be specific when giving instructions, and to be aware that what’s in your current chat will form part of the context window for whatever you’re asking.

The Unfortunate Part – What You Cannot Control

Lawyers generally appreciate control. Being able to manage a given situation is important to us. Unfortunately, you can’t control the entire context engineering in the AI tools you’re probably using. Not unless you’ve had them customized for your use.

ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini and other consumer AI tools let you write prompts and upload documents. That’s pretty much it. You can’t modify chunking algorithms. You can’t change retrieval ranking. You can’t see or edit system prompts. You can’t control what examples the model processes. The interface hides all of it.

Legal-specific tools like Westlaw AI, Lexis AI, CoCounsel, and Harvey give you slightly more control, maybe. Upload documents to matter workspaces. Set some basic filters. That’s usually the limit. You’re still subject to vendor context engineering decisions about chunking, ranking, and architecture.

Enterprise contracts with custom configurations might let firms upload precedent libraries, adjust some retrieval settings, or specify output formats. Even then, you typically can’t touch core architecture—the chunking algorithms, base system prompts, or ranking weights that determine whether the tool works well for legal documents. Unless you hire an expert to make modifications.

So if you can’t control context engineering, why does understanding it matter?

You Still Need to Understand It

Understanding context engineering gives you the advantage of significantly more high-quality responses from your AI output.

First, More Effective Use of AI. Recognition of what the problem is and what’s causing it matters because it changes how and when you use AI. Instead of assuming all AI tools are equally unreliable and avoiding them entirely, you understand that some tools fail because of fixable context engineering while others have architectural problems that make them unsuitable for legal work regardless of prompt quality. Understanding limitations and capabilities makes AI significantly more useful.

Second, Professional Responsibility. ABA Model Rule 1.1, Comment 8 requires maintaining competence regarding the benefits and risks of relevant technology. You can delegate execution but not understanding. When a court asks how your AI tool reached a conclusion and your answer is “I don’t know, I just used what the firm bought,” that sounds to me a bit like incompetence. You need enough literacy to evaluate whether tools are suited to your tasks, recognize when outputs are unreliable, and explain your quality assurance process when questioned, especially if you’re questioned by the court.

Third, Vendor Evaluation. Someone at your firm is evaluating AI tools, negotiating contracts, setting AI policies. If nobody understands context engineering, those decisions get made based on price, brand recognition, and whatever the sales demo emphasized. The actual architecture determining output quality never gets evaluated because nobody knows to ask about it. Vendors claim their AI tool is “optimized for legal work” or “trained on legal data” or “purpose-built for law firms.” Those phrases mean nothing without understanding context engineering. Optimized how? Trained on what? Purpose-built with what architecture?

Understanding context engineering gives you the vocabulary to ask questions that expose substance versus marketing. Does their chunking preserve legal document structure? How does their retrieval handle jurisdictional hierarchy? Can you see their system prompts? Do they maintain audit trails? These questions separate serious vendors from the smoke and mirrors of glossy advertising. Part 2 of this article gives you questions you can ask vendors.

Context Engineering to Improve Your Output

You saw the unfortunate parts about context engineering, and how little we users can control it. Better prompts won’t fix bad chunking. Better prompts won’t change retrieval ranking, expand context windows or improve cross-reference handling.

But never fear, because there are simple techniques that don’t require you to understand a chunking strategy or retrieval ranking. Adopt these today to make sure you are making the most of context engineering constraints.

8 Best Practices for Using Context Engineering to Your Advantage

Don't Mix Chats. Keep each matter, project, or task in its own conversation thread rather than bundling unrelated work into one sprawling session. Mixing chats pollutes the context window with irrelevant material, diluting focus the same way a cluttered trial exhibit binder dilutes yours.

Use GPTs, Projects, and Workspaces. Take advantage of your tool’s built-in organizational features to create dedicated spaces for specific matters or practice areas. These features pre-load relevant context and keep your documents organized in ways the AI can actually access—think of them as your AI’s filing system. Not sure how to set up a custom GPT? Learn how in less than 10 minutes.

Give Positive Reinforcement and Specific Feedback. Tell the AI when it gets something right (“that's exactly the format I need”) and redirect with precision when it doesn’t (“the risk levels need to be more granular”). Positive feedback anchors good behavior within the conversation while specific corrections steer outputs toward your standards without wasting context on repeated failures.

Delete Old Documents. Remove documents from your workspace or conversation that no longer serve your current task. Old documents consume valuable context window space, quietly crowding out the material that actually matters—like briefs nobody asked for, taking up space in a judge’s chambers.

Summarize Long Documents, Then Delete the Originals. Ask the AI to summarize lengthy documents first, then work exclusively from those summaries. Summaries preserve substance while freeing context window capacity for the analysis you actually need—hello efficiency without sacrifice.

Start a New Thread. On an especially complicated matter, or if your context window is low, start a new, clean thread. You can import the summaries mentioned in #5 above into it. Deleting old documents won’t guarantee that they’re removed from context, and it may not reduce the current context window.

Point Your AI to the Right Material. When working with multiple versions, meeting notes, or memos, explicitly reference which one applies to your current question rather than leaving the AI to guess. Undirected tools default to whatever context surfaces first, which is rarely correct.

Use Exemplars. To save context window space, it can make sense to include an exemplar, or ideal example of what you want the AI tool to create. This takes advantage of a technique called “few shot learning.” Note if the exemplar is extremely long, contains a lot of graphics or special formatting, this technique might backfire on you and take up too much of your context window. Be mindful if employing this technique.

What Comes Next

Understanding context engineering matters because it transforms how you use AI tools, but also how you evaluate and select AI tools. You can’t engineer context in most tools, but you can use best practices to take advantage of the context engineering you’re stuck with.

My next article addresses vendor evaluation specifically.

How to expose context engineering quality during demos.

What questions reveal architectural substance versus marketing smoke.

What contract terms and testing protocols ensure you’re buying tools that can actually work for legal applications.

A basic understanding of context engineering (this Article), along with some specific questions and tests that help you with tool evaluation (next Article) requires understanding what you’re evaluating. And the better you understand AI tools, the better shape you’re in to make the most of the AI tools you use.

© 2026 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.

Legal Fees Aren’t Going Down Despite AI Adoption in Law

AI has made BigLaw faster and more profitable—but not cheaper. Instead of expanding access to justice, efficiency gains are flowing upward, leaving legal costs high and the justice gap intact.