February 19, 2026

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

Considering Using an AI Agent? Here are the Things You Should Know but Don’t

Of all professionals, lawyers should be the least surprised when delegation creates liability. We spend careers analyzing principal-agent relationships, parsing scope of authority, and litigating whether someone acted within their delegated powers. We know that when you appoint an agent, you're responsible for what they do within the authority you've given them.

Yet somehow, when the agent is artificial rather than human, we forget centuries of jurisprudence and treat it as a productivity tool instead of a legal actor. This is not a metaphor. When you deploy an autonomous AI system with authority to access documents, draft communications, and make decisions on your behalf, you've created an agent in the legal sense. The fact that it runs on silicon rather than neurons doesn't change the analysis.

Consider what happened to Clawdbot in early 2025.

The Clawdbot Disaster (Agency + Autonomy = Chaos)

Clawdbot promised to be the personal AI assistant everyone wanted. Autonomous, capable, always-on. It connected to WhatsApp, Telegram, Slack, Signal, iMessage, email, and calendars. It could execute shell commands and maintain persistent memory across your entire digital life. It was genuinely agentic, designed to act independently toward objectives you set.

Within 72 hours of going viral, security researchers documented what they generously termed a "dumpster fire." Over 1,000 exposed servers. Prompt injection attacks that exfiltrated credentials in minutes. Plaintext storage of API keys and OAuth tokens (a huge security no-no). A proof-of-concept supply chain attack through the community skills repository.

The CEO of Archestra AI demonstrated the most elegant attack. He sent a crafted email to an inbox Clawdbot was monitoring. When the agent processed the message, injected instructions caused it to search the filesystem and exfiltrate a private SSH key. No direct system access required, just content the agent would read and dutifully execute.

This wasn’t a mistake per se. The agent was doing exactly what it was authorized to do. It read email. It accessed files. It executed commands. It followed instructions. Every action was formally within scope. The problem was that the model simply couldn't distinguish "process this email" from "rummage through ~/.ssh and exfiltrate keys."

In agency law terms, the agent acted within its apparent authority. The principal is liable. That the principal didn't intend the specific action is irrelevant. That's how agency works.

Lawyers Should Know Better

Every first-year law student learns the basic framework. When you appoint an agent, you're liable for their acts within the scope of authority you've granted. Actual authority, apparent authority, ratification after the fact—the details vary but the principle doesn't. The agent's conduct becomes your conduct for legal purposes.

This applies whether your agent is a summer associate, a registered agent for service of process, or an AI system you've authorized to access client files and draft legal documents. The medium of agency doesn't change the liability allocation. If anything, AI agents create more exposure because their scope of authority is often poorly defined and their actions are harder to monitor.

When you deploy an agentic AI system, you're making an agency appointment. You're delegating authority to act on your behalf. The fact that you did it through a configuration file instead of an engagement letter doesn't change the legal character of the relationship. And just like with human agents, you remain liable for what they do within their delegated authority, whether you specifically authorized each action or not.

Agentic vs. Agent-ish

The term "agentic" gets misapplied to everything with a chat interface and a ‘for-loop.’ Let's be precise, because the distinction determines your exposure.

Agentic systems take objectives and autonomously determine execution. They plan, act, and adapt based on context. If you stop typing, they keep working toward the goal. They don't wait for permission at each step. They operate within delegated authority until they hit an escalation trigger you've defined.

Agent-ish systems chain tasks together but remain fundamentally reactive. They execute predefined workflows or respond to explicit prompts. Remove the human steering and they stop. They're sophisticated automation, not autonomous actors.

The distinction maps to familiar legal roles. Agent-ish is like a paralegal with a detailed checklist. You assign each task explicitly, review the work, then assign the next task. Efficient but requiring constant supervision. Agentic is like a junior associate with limited authority. You set the objective ("draft the motion, pull exhibits, format for filing") and they determine the sequence, escalating judgment calls as needed.

The test is simple. If you stop typing, does it keep advancing the work?

Agentic acts. Agent-ish assists. That difference determines whether you're supervising a tool or managing an agent relationship.

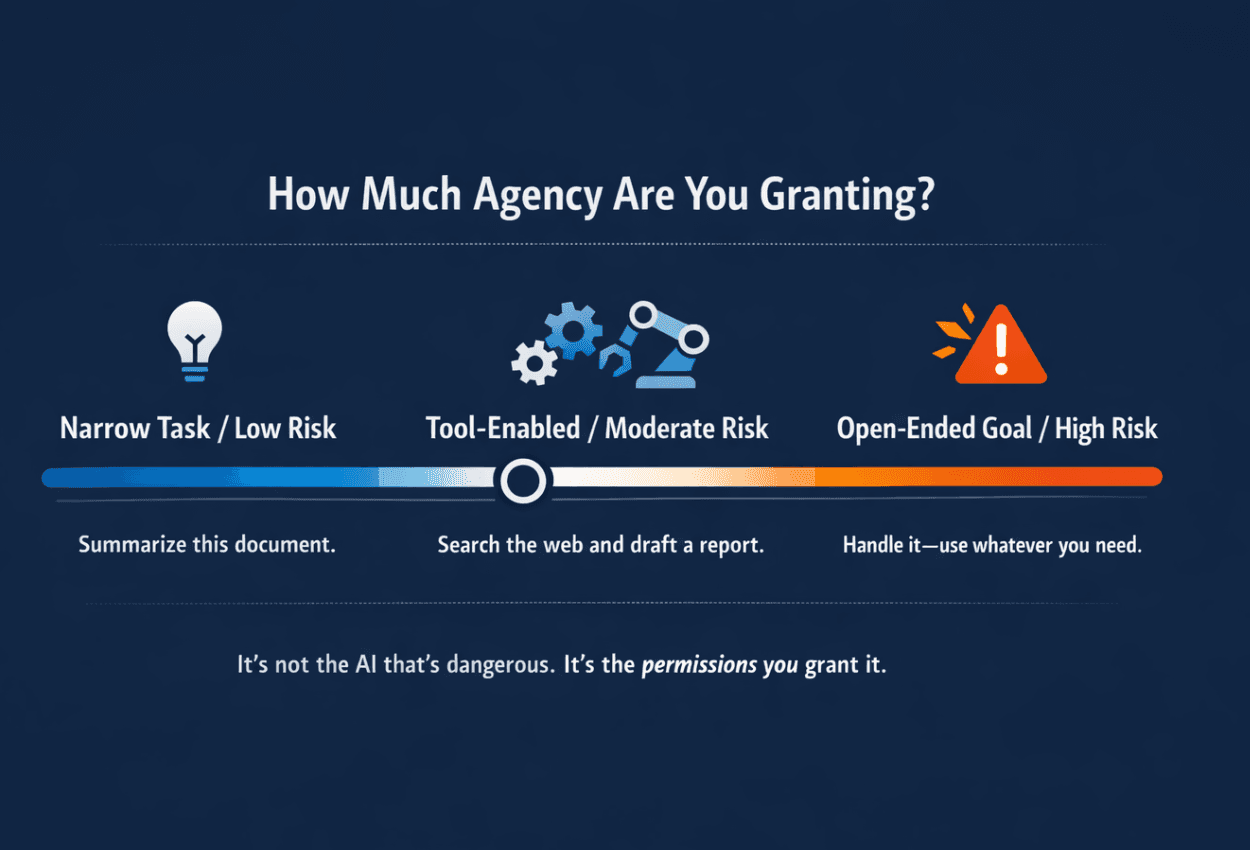

The Authority You Delegate Defines the Liability You Own

Here's where lawyers' professional training should provide an advantage but somehow doesn't. We understand that authority and liability travel together. When you give an agent authority to act, you accept responsibility for their actions within that scope. Narrow the authority, limit the exposure. Broaden the authority, accept the risk.

AI agents follow the same principle with a dangerous twist. The authority you delegate is defined by system configuration, not clear instructions. An AI agent with read access to your document management system has authority to access everything in that system. Whether you intended it to search privileged communications or only review contracts is irrelevant. You gave it access. That's the delegation.

The Clawdbot prompt injection demonstrates this problem. Users delegated authority to process email and execute commands. They didn't specifically authorize credential exfiltration. But the authority they did delegate was broad enough to encompass those actions when an attacker provided the right instructions. The agent stayed within its technical permissions even as it violated its principal's intent.

In traditional agency relationships, we manage this through clear scope definitions, regular oversight, and aligned incentives. Your associate knows not to disclose privileged information even though they have access to it. Your paralegal understands confidentiality obligations. AI agents have no such internalized constraints. They have permissions and instructions. That's it.

The Clawdbot Failure Modes (And Their Legal Parallels)

Clawdbot's failures aren't hypothetical edge cases. They're predictable consequences of agentic design meeting inadequate governance. Each maps directly to legal practice vulnerabilities.

Spoiler Alert -- This is a bit technical, jump to the next section if you do not care.

Misconfigured exposure happened when users placed Clawdbot behind reverse proxies that treated public internet traffic as localhost, bypassing authentication. Anyone could hit the control panel, view configuration, trigger commands. For lawyers, substitute your AI contract analysis tool exposed to the internet through VPN misconfiguration. Opposing counsel sends a document for review. Your agent processes it, extracts strategy notes from prior matters, and helpfully includes them in the analysis. You just waived privilege through technical incompetence masked as efficiency.

Prompt injection leading to credential exfiltration was Archestra's elegant demonstration. Send content the agent processes, inject instructions that redirect normal functions. For legal AI, the attack vector is any uploaded document. An adversary embeds instructions in metadata or hidden text. Your agent, designed to be helpful and operating within its delegated authority, extracts confidential information from your document management system and incorporates it into the output. You've disclosed protected work product because your agent couldn't distinguish legitimate instructions from malicious ones. The agent had authority to access those files. It used that authority. You're responsible.

Plaintext credential concentration meant Clawdbot stored API keys, OAuth tokens, and conversation logs in predictable plaintext files. Infostealer malware began targeting these locations within days. Legal AI agents require credentials for document systems, research databases, client portals, email. Concentrate those in plaintext storage and you've created a single point of catastrophic failure. One compromised endpoint exfiltrates credentials for every system your firm uses. Every client matter potentially exposed through one security failure.

Unvetted skills supply chain let Clawdbot users install community-contributed "skills" that extended the agent's capabilities. A researcher uploaded a benign skill, inflated download counts, and watched developers across seven countries install and execute it with full trust. Legal AI platforms increasingly offer plugin ecosystems and third-party integrations. Each one is a potential supply chain attack vector. That contract analysis plugin you installed might be exfiltrating client data while performing its advertised functions perfectly. You delegated authority to the plugin when you installed it. You own what it does.

AI Agents Have No Fiduciary Duty (And That's the Problem)

When you delegate authority to a human agent, multiple safeguards operate simultaneously. The agent owes you fiduciary duties. They face professional consequences for misconduct. They have career incentives aligned with your interests. They exercise judgment that incorporates unstated but understood constraints. Your paralegal knows not to disclose privileged information even when technically authorized to access it.

AI agents have none of this. No fiduciary duty. No professional liability. No reputation to protect. No internalized understanding of legal privilege or confidentiality obligations.

Best Practices a.k.a. Governance for Agent Relationships

The more autonomous your agent, the more rigorous your controls must be. Keep in mind that when you adopt an agentic workflow, you’re managing an agency relationship with an entity that has broad authority, no judgment, and no fiduciary obligations. If that sounded scary, it should.

Minimum necessary authority. Give your AI agent minimum authority required for its specific function. For example, Contract analysis gets access to the contract repository only, not the entire DMS, not email, not work product folders. Research gets read-only access to research databases, not client files.

Start small, fail safely. Do not start with legal research, strategic analysis, or client advice – those are all things that AI is *not* good at. This is where you add value as a lawyer.

Use small, narrow agents. Build multiple narrow agents instead of one agent with expansive ‘god-mode’ permissions. If an agent is compromised, the breach should be contained to that agent's limited scope, not cascade across your practice, exposing client confidentiality, or work product privileged material. If you can't audit the code or verify provenance, don't deploy it with client data.

Explicit escalation triggers. This is just a fancy way of saying “define when the agent must ask for human review.” Don't allow autonomous judgment on matters requiring professional discretion. For example, any action involving client communication, court filings, or legal conclusions requires explicit human approval.

Comprehensive audit logging. Run audits and keep audit logs. This will keep you in control, and it creates the record you'll need when things go wrong.

Credentials Separated. Make sure your AI agent doesn’t have access to your encrypted storage. Keep your most confidential information in storage that your AI agent doesn’t have access to.

Vetted integrations only. Before giving an AI agent access to your system, either prohibit access to the app’s you’ve integrated or make sure you know what will happen—worst case—when your AI agents goes live. This is a preventable vulnerability that is often overlooked.

No access to public internet. If you are new to an AI agent, one of the simplest and easiest to implement controls is, ‘don’t allow access to a public internet connection.’ This will go a long way in keeping your own information safe.

Human-In-Control. Make oversight practical rather than theoretical. If the agent cites cases, it provides direct links to verify them. If it analyzes contracts, it surfaces the specific language being analyzed. Don't rely on post-hoc review. Build verification into the workflow so people will actually do it instead of rubber-stamping output.

Your Ethical Obligations Haven't Changed

Model Rule 1.1 requires competence. Model Rule 1.3 requires diligence. Model Rule 1.6 requires confidentiality. Model Rule 5.3 requires supervision of non-lawyer assistants. These rules contain no AI exceptions and no technology carveouts.

When you deploy an agentic AI system, you remain responsible for competent output ("the agent hallucinated that case" is not a malpractice defense), client confidentiality (every input to your agent is a potential disclosure, every vulnerability a potential breach), adequate supervision (you can't supervise what you can't audit), and work product protection (AI-generated documents carry metadata that might undermine privilege, and compromised agents can exfiltrate privileged material).

Agency Law Still Applies

Agentic AI offers genuine value when deployed with appropriate controls. The technology enables you to delegate routine execution while focusing on strategy, judgment, and client counseling—all the things that machines can’t do. But delegation without governance is negligence, and lawyers should know this better than anyone. Agency law applies whether your agent is carbon-based or silicon-based.

© 2026 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

Agentic AI in Law

Deploying an autonomous AI in your practice isn’t using a tool—it’s appointing an agent, and you’re liable for what it does within its authority.

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.