January 14, 2026

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

Part 1: Why Conversational Data Creates Unique Legal Risk

You join a Zoom call to discuss settlement strategy. Three colleagues from your law firm’s offices in different cities appear on screen. But there's a fourth participant—one that you weren’t aware was invited. In fact, it may not even be visible: an AI notetaker bot. The AI note-taking bot records the audio, transcribes every word, captures screenshots of the video, extracts participant names and emails from the calendar invite, and perhaps even generates a persistent voiceprint for each speaker.

Even if a colleague asks if you mind them recording the meeting as a notetaker, you might not give much thought to this, since the meeting is only among lawyers at the same firm.

But what happens to the data that the AI notetaker bot gathers and what it does with that data should give you pause. Unfortunately, your data most likely does not sit quietly in a dark electronic file. Rather, all of your data flows to the vendor’s servers, where it may be used to train the company’s proprietary AI models.

AI Notetaker Bots Are Now the Norm

The scenario is far from hypothetical. During Covid, we gained a level of comfort with virtual meetings. For better or worse, professionals in the same city now regularly take meetings virtually where several years ago we would have driven 15, 20 or even 30 minutes to meet in person. Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and Zoom have made AI transcription a default feature, not an add-on. Otter.ai boasts that it has transcribed over one billion meetings.

I will usually gamble on getting the service I am hoping for by engaging the online chatbot that continually pops up in the lower, right-hand corner, reminding us of its willingness to assist. These days such chatbots are generally equipped with a warning “this conversation may be recorded to improve our blah blah blah.” Boring, right? I’m a lawyer and AI expert, and I barely glance at those warnings. And the warnings on the telephonic bots are equally as bland and non-descriptive, especially in light of what the system capturing this data is doing with it.

AI-powered transcription has become workplace infrastructure. A 2025 survey found that 22% of legal professionals use AI transcription tools for client meetings, depositions, and internal strategy sessions. Adoption rates are higher in large law firms (approaching 40%) and continue to climb as vendors integrate transcription features directly into video conferencing platforms. What started as a pandemic-era convenience has become embedded in professional workflows.

The contact-center industry has adopted AI transcription at even greater scale. Google Cloud Contact Center AI, Amazon Connect, and similar platforms process millions of daily customer service calls through systems that transcribe conversations in real time, analyze sentiment and intent, generate suggested responses for human agents, and store call data for quality assurance and analytics. For enterprises handling customer service at scale—telecom providers, retailers, financial services, healthcare—AI transcription is no longer optional infrastructure.

Why We Should Pay Attention to the Bot Disclaimers

Many users, including lawyers, do not fully understand the data flows these tools create. A meeting transcript is not merely a text file saved locally. Depending on the vendor's architecture and terms of service, it may include audio files, video screenshots, participant metadata pulled from integrated calendars and contact lists, persistent speaker identification across multiple meetings, and contractual permissions allowing the vendor to use all of this material to “improve services” or train AI models. The gap between user expectations (“I'm just recording this meeting for my notes”) and vendor capabilities (“we reserve the right to use your data for product development”) is where litigation risk emerges.

Recent class actions signal that this risk is materializing. In re Otter.ai Privacy Litigation challenges Otter's AI meeting assistant under federal wiretap law, California and Washington state privacy statutes, and Illinois' biometric privacy law. Ambriz v. Google targets Google's contact-center AI platform, arguing that Google intercepts customer service calls as an undisclosed third party. Both cases share a common theory: AI vendors that record private conversations and use the resulting data to train commercial models are statutory eavesdroppers, not neutral productivity tools.

Here's why conversational data matters for AI training.

If Data is Fuel for LLMs, Conversations are High-Powered Rocket Fuel

Most public AI litigation still focuses on models trained on scraped web data—authors and creators objecting to their published work being appropriated for training datasets in cases like Kadrey v. Meta and Bartz v. Anthropic. While those cases remain important, AI note-taker litigation highlights a different and potentially more valuable data source: live, high-signal conversational data from meetings and customer service calls.

Conversational data has characteristics that make it uniquely valuable for training AI models, particularly for conversational agents, summarization tools, and task-oriented reasoning systems.

Live Conversations Are Scarce and Highly Structured

Real-time recordings and transcripts of meetings and calls capture detailed, candid information about problems, decisions, and strategies in ways that scraped web text cannot. Customer service calls, internal strategy meetings, legal consultations, therapy sessions, and technical support interactions are not random collections of words. They are contextual and labeled. Who is speaking, what problem they are describing, and how it gets resolved are often explicit in the conversation. These conversations are domain-rich, reflecting actual workflows in finance, healthcare, law, HR, and technical support.

In contact-center environments, they are outcome-linked, tied to CRM records showing whether the issue was resolved and whether the customer was satisfied.

For an AI vendor, this is extraordinarily valuable training material. Compared to generic scraped text, conversational streams improve intent recognition, summarization accuracy, and task-oriented reasoning in exactly the domains enterprise buyers care about. If scraped web data is like reading every published case and law review article, live conversational data is like recording every confidential client consultation, jury deliberation, and settlement conference.

Virtual Meetings Create Multi-Modal Training Datasets

The consolidated complaint in Otter.ai illustrates how a simple “note-taker” can extract multiple data layers from a single meeting. Plaintiffs allege that Otter Notetaker transcribes the full conversation and ties words to timestamps, captures screenshots of the video call, pulls identity metadata such as names, emails, and contact details from Zoom, Teams, Google Calendar, and Outlook, and generates and stores a persistent voiceprint for each speaker, allegedly recognizing those speakers across future meetings.

Legally, this transforms a single meeting into a bundle of:

content (what was said),

context (who said it, when, and with whom),

imagery (who was on screen), and even

biometrics (voiceprints used for speaker identification).

For AI vendors, this multi-modal dataset—audio, transcripts, screenshots, metadata, and biometric voiceprints—is far more valuable than scraped web text for training conversational AI models. It allows vendors to improve speech recognition, speaker diarization (determining who said what), sentiment analysis, and contextual understanding by learning from real professional conversations.

From a privacy and liability perspective, however, this looks less like the transcript of a random meeting and more like systematic extraction of private communicative and biometric data without meaningful consent or disclosure.

Otter.ai Recognizes The Value of Conversations

The economic value vendors place on conversational data is evident in how they market these tools. One of Otter.ai's founders, Sam Liang, has recently published a post confirming this strategic value. For example, in a LinkedIn post celebrating the company's growth, he described meeting transcripts as “the dominant system of record” for enterprises, describing conversations as capturing “truth” and decisions before they become formalized documentation. While this marketing describes value delivered to customers (helping companies organize their own meetings), it underscores why conversational data is attractive for AI training. Specifically, meetings contain authentic, contextual, outcome-linked information that static documents lack. The same characteristics that make meeting data valuable for customer knowledge management make it valuable for training conversational AI models.

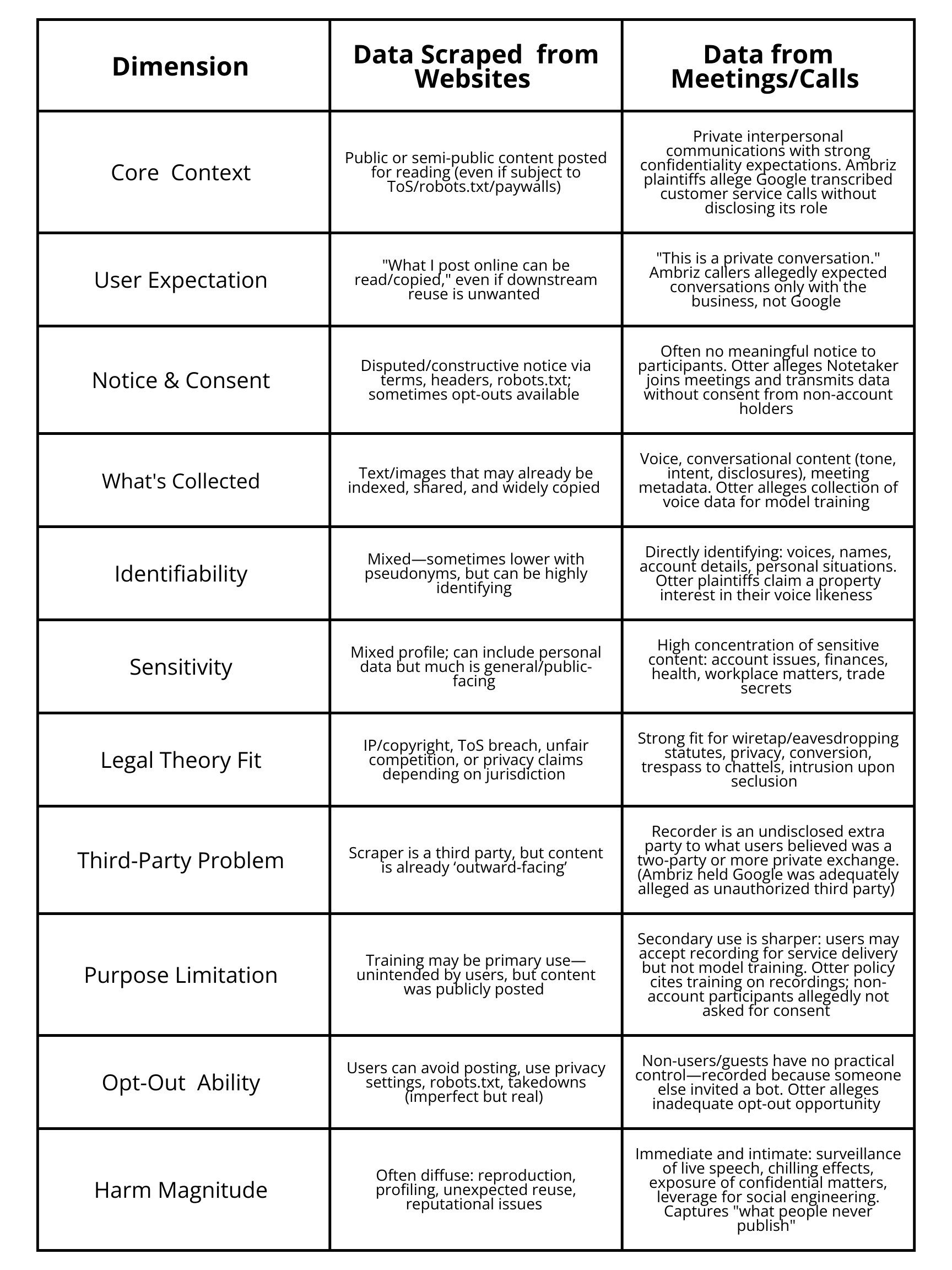

Conversational Data vs. Web Scraping

Public debates around AI often center on whether scraping websites constitutes copyright infringement or fair use. I’ve studied scraped data litigation in depth. This conversation data capture operates in an entirely different legal framework. Training on private conversations is categorically more invasive than web scraping—it converts private speech into reusable training assets without meaningful consent or transparency.

The following table illustrates the legal and practical differences:

This comparison reveals why conversational data creates legal exposure that web scraping does not. The underlying conversations were never intended to be public. They can involve professional confidences, medical information, or business strategy. The data collection implicates wiretap law, biometric statutes, and privacy torts—not just copyright. And reidentification is easy. Even with names removed, distinctive context (a company's specific problem, a customer's account details, a lawyer's legal strategy) often reveals who was speaking.

Otter.ai Acknowledges Training Its Models on Recorded and Transcribed Meetings

Otter.ai publicly acknowledges using customer meeting data to train its AI models, making the legal vulnerability discussed in this series concrete rather than theoretical.

According to Otter's Privacy & Security page, “Otter uses a proprietary method to de-identify user data before training our models so that an individual user cannot be identified.” The company’s Terms of Service specify that while customers retain ownership of “User Content,” they grant Otter a broad “worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to host, store, modify, process, and distribute that content as needed to provide the service and related functionality.”

Otter’s Privacy Policy states that personal information may be processed for purposes indicated in the policy or as otherwise notified to users, and that Otter may transfer personal data to third parties consistent with those purposes.

External analyses confirm that Otter obtains this permission through account settings where users check a box allowing Otter to access private conversations for training and product improvement. Critically, this consent mechanism operates at the account-holder level—the person who brings the Otter bot to a meeting—not necessarily from all meeting participants.

Here’s what makes Otter.ai’s practices so dodgy. A meeting participant might not even realize that they are being recorded by Otter.ai. That their image, voiceprint, and statements might be used by Otter in various ways. Otter’s ToS state, “You acknowledge and agree that you are solely responsible for providing any notices to, and obtaining consent from, individuals in connection with any recordings as required under applicable law.” In this way Otter.ai is attempting to transfer responsibility and likely liability to the person or entity using Otter.ai as their notetaker.

And that situation of not even being aware of the recording or transcription plays into Plaintiffs’ complaints in the consolidated litigation. When an Otter user enables training and joins a meeting with non-consenting participants, Otter’s contractual right to use that meeting data for model training purportedly converts Otter from a neutral transcription service into a third-party interceptor extracting valuable data without all-party consent.

The “Deidentification Defense” Fails

Some AI vendors, Otter.ai among them, claim they only train on deidentified data, suggesting this mitigates privacy concerns. In the conversational AI context, this defense is less effective than it appears and may actually increase litigation risk by demonstrating that the vendor recognized the data's sensitivity but failed to adequately protect it.

Conversational records are unusually resistant to effective deidentification. Even when direct identifiers like names are removed, context often reidentifies speakers or organizations. A customer service call about a billing dispute for a specific account, a legal consultation about a pending acquisition, or a therapy session discussing a particular diagnosis all contain enough detail that removal of the speaker's name does not render the conversation anonymous. When datasets also include audio files, video screenshots, or voiceprints, the concept of deidentification becomes meaningless—the voice itself is a biometric identifier.

Deidentification Isn’t Really Deidentification

Otter.ai’s privacy policy gives a false sense of security in regard to the use of the information gathered by Otter.ai in these meetings. You see, deidentification isn’t really deidentification. As discussed above, conversational data resists meaningful deidentification because context reveals speaker identity even when names are stripped. Moreover, Otter.ai acknowledges that once meeting data enters the training pipeline, as a practical matter it is not removable from already-trained models even if you later delete the source data. From a litigation perspective, this admission is significant; it confirms that Otter's use of meeting data is not temporary or ephemeral but results in permanent incorporation into Otter's commercial AI products. This supports the Otter.ai Plaintiffs' conversion claims such as permanent appropriation of valuable personal property.

The combination of admitted training practices, broad license terms, and account-holder-only consent creates exactly the exposure that seems as though it should be actionable. Plaintiffs are using older laws such as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) to various state privacy laws in order to pursue claims, as discussed in depth in Part 2 of this series.

Otter’s Software Services Agreement for enterprise customers may provide additional protections, but the core tension remains: when AI vendors reserve contractual rights to use meeting data for their own model training, they transform themselves from service providers into data extractors—precisely the characteristics that can transform meeting transcription tools into electronic eavesdroppers.

Meeting Transcription or Electronic Eavesdropper?

This lack of ability to de-identify plays directly into plaintiffs' legal theories. When a vendor has economic incentive to retain and reuse conversational records (to train models that will be sold to other customers), plaintiffs argue the recording was not incidental to providing the requested service. Instead, it was appropriation of something with real market value. The same commercial incentive supports plaintiffs' "tortious purpose" arguments under federal wiretap law: the interception was undertaken not merely to provide meeting notes or call transcripts, but to extract private communications and biometrics for the vendor's own enrichment.

The cycle is self-reinforcing. The more valuable conversational data becomes for training large language models, the more plaintiffs can argue that AI vendors operate data extraction businesses disguised as productivity tools. That characterization in turn supports claims of intrusion upon seclusion, conversion, unjust enrichment, and violations of the “tortious purpose” exception to one-party consent under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act.

We are so used to seeing AI notetaker bots that many of us are not concerned by whether one or more are in attendance. But in ignoring the attendance of these tools has potential repercussions that we are not aware of.

AI transcription tools are undoubtedly useful. But consumers and unwitting, uninformed meeting participant should be made aware of what is likely happening to their data when AI notetakers in general--and Otter.ai in particular--are attending the same meeting they are.

Next Article . . .

Statutory and Case Law Defining the Rights of Parties Part 2

Recent class actions challenge AI note-taker and contact-center tools under three primary legal frameworks, each of which will be examined in detail in Part 2 of this series.

Federal wiretap law (the Electronic Communications Privacy Act) repurposed into a tool used with AI recordings and transmissions;

California's Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA), which requires all-party consent for recording many communications and provides a private right of action with statutory damages of up to $5,000 per violation; and

State biometric privacy laws, led by Illinois' Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), which regulate the collection and storage of biometric identifiers including voiceprints.

© 2026 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

Agentic AI in Law

Deploying an autonomous AI in your practice isn’t using a tool—it’s appointing an agent, and you’re liable for what it does within its authority.

The SaaS-pocalypse -- What Claude Cowork Means for Law

The real disruption isn’t that AI replaces lawyers—it’s that it destabilizes per-seat software pricing, automates commoditized legal work, and gives clients new leverage to challenge how legal fees are structured.

Fix Your Context Engineering to Fix Your Output –8 Valuable Tips

Even the perfect prompt cannot rescue bad context engineering—because what your AI sees, structures, and prioritizes behind the scenes determines your output at least as much as the question you type.