February 3, 2026

AI in Legal Practice

Amy Swaner

AI Is Optimizing BigLaw—Not Access to Justice

In the beginning of GenAI in law, there was a hope among some—including me--that widespread access to artificial intelligence would reduce legal costs, expand access to justice, and level a playing field that is noticeably tilted toward those who can afford $800-an-hour legal counsel. Technology could deliver what pro bono hours and legal aid budgets could not—affordable legal help for the 92% of civil legal needs of low-income Americans that go unmet. That hope skipped over optimism and landed directly in the category of naïveté.

Three plus years into the generative AI boom, here’s the reality:

The efficiency gains of AI are real. The cost reductions in legal services are not.

The Profit Paradox

Axiom's relatively ancient 2024 study of 600+ senior legal leaders across eight countries reveals the mechanics of a profit paradox: 79% of law firms now use AI to boost efficiency. Only 6% pass those savings to clients (summarized in this July 2025 Axiom blogpost). Better still—if you're a partner—34% charge premium rates for AI-enhanced work. Id.

I’ve never been amazing at math, but these equations look quite elegant. An AI tool completes in two hours what previously took ten. The client still pays for ten or maybe pays a premium for “cutting-edge AI-enhanced service.” The associate bills less. The partner pockets the spread. Corporate legal departments, already squeezed, find themselves funding their outside counsel’s AI transformation while seeing none of the financial benefits. It’s no surprise that inhouse counsel’s adoption of GenAI dwarfs regular law firms’ adoption, since the inhouse teams can show the cost savings from AI efficiency gains.

Opinion 512’s Effect (Or Lack Thereof)

But what about Opinion 512 you ask? Doesn’t that force downward pressure on legal bills if we are obligated to only bill for actual time, and can’t bill for AI tool costs without disclosure to the client? True, if billing hourly Opinion 512 says lawyers “must bill for their actual time” and may not bill “for more time than [they] have actually expended.” The problem is that we aren’t seeing lower legal fees. Corporations wonder why their bills from outside counsel haven’t been reduced by AI efficiency gains.

There is a dearth of evidence that legal fees have gone down appreciably. What I found instead is evidence that despite legal’s adoption of AI tools, there’s no sign that legal rates are going down. In BigLaw, where AI adoption is highest, pricing keeps climbing. According to one report, billing at AmLaw 100 firms jumped 8.3% going into 2025. Recent data from a Wells Fargo survey reported that the 200 largest US firms saw revenue grow roughly 13% in 2025 as billable rates rose nearly 10%. Top 50 firms’ rates were up 10.4% in a single year. Commentary suggests the increase was driven by rate hikes, not increased demand.

Market discipline prevents voluntary repricing even among the most well-intentioned law firms. Cut rates too aggressively and you signal either desperation or an admission you've been overcharging for years. Neither plays well at lateral recruiting dinners or client pitches. Better to maintain rates, improve margins, and deploy AI as a competitive moat rather than a client gift.

The result is wealth concentration that would make John D. Rockefeller blush. AI is enriching the biggest firms. AI also delivered around 7%+ household wealth gains (per Oxford Economics), but those gains flow upward—to shareholders of legal tech companies, partners capturing efficiency spreads, and corporate clients who’ve built internal AI capabilities to bypass outside counsel entirely. Hence, the K economy.

The ‘Special’ K Economy

No disrespect to Kellogg, we’re in a ‘special’ K economy. The letter K has two branches diverging from a common stem. One ascends; one descends—never to meet again. Post-2008 financial crisis, economists noticed recovery wasn't uniform. High-income households and white-collar workers rebounded quickly (ascending branch). Low-income workers and service industries stayed depressed or declined further (descending branch). The shape of their respective trajectories, when plotted, resembled a K. COVID accelerated the pattern. Tech workers Zoomed meetings from home while service workers lost jobs, burned savings, faced eviction, and hardly saw an increase in their base pay. Same pandemic, opposite outcomes. The branches diverged sharply.

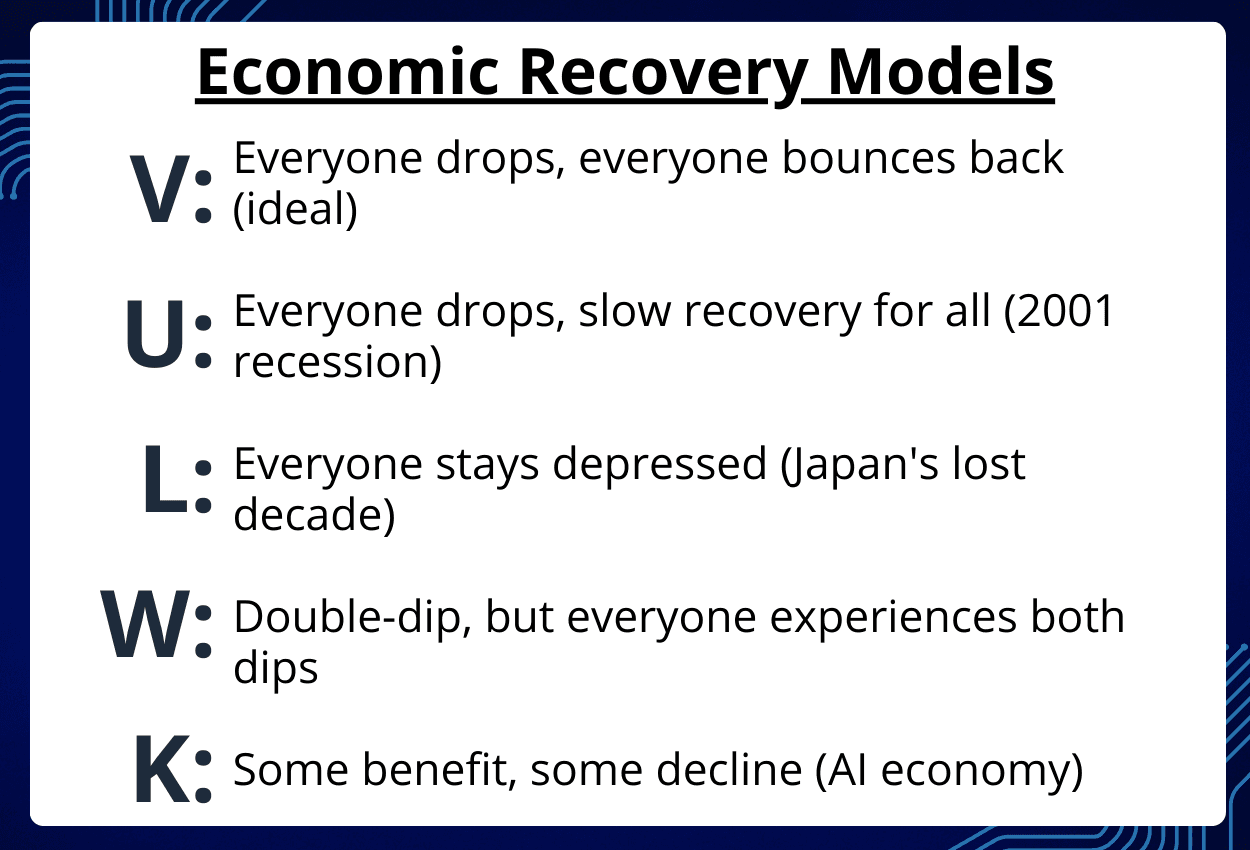

Contrast the K economic recovery with other recovery shapes:

Oxford Economics CEO Ian McFee offers this insight: AI doesn't create a V (rising tide lifts all boats). It creates a K. And that K stays locked for a decade minimum—the time required for productivity gains to trickle down to workers whose labor AI can’t replace. The K is pernicious because there’s no collective recovery. No celebration to rally and unify. Some households celebrate record quarters while the others look for the local food bank. There is no “economy” that we're all experiencing together.

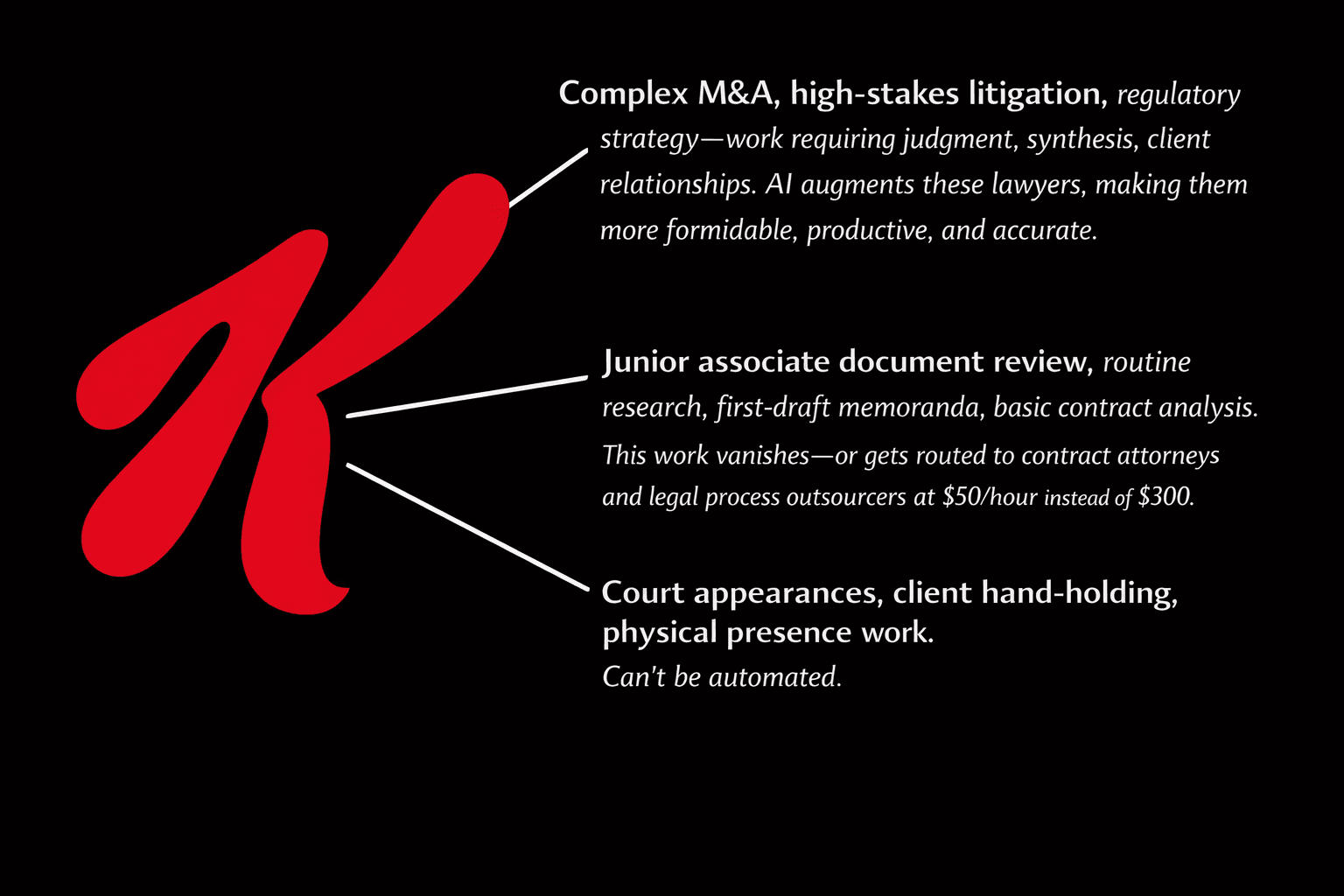

The K-Shaped Economy Comes to Law

Oxford Economics projects the AI-driven wealth divergence will persist through 2035. Legal services mirror the greater economy: AI delivers efficiency gains, but capital captures them first—and longest. The top 0.1% saw wealth grow 281% from 2010 to 2025, reaching $24.89 trillion. The bottom 50% grew faster in percentage terms (1,189%) but still hold only $4.25 trillion combined. Six times less than the wealthiest one-tenth of one percent. Id.

The Upward Branch of the K

BigLaw partners, corporate general counsel, and legal tech investors ride the ascending branch of the K. EDiscovery is a prime example. Document review that cost $200,000 now runs $30,000—but clients rarely see the whole $170,000 savings. Firms either maintain rates (billing for value rather than hours) or charge premiums for AI-enhanced service, or in most cases, land somewhere in the middle. Regardless, profits per partner rise rather than lower.

According to a recent Forrester study commissioned by LexisNexis, corporate legal departments deploy AI to reduce outside counsel spend by 13%, keeping work in-house. That is a tidy savings. One recent article calls AI ‘"the hottest cost-cutting tool in corporate legal departments.” General counsel become budget heroes. The savings flow to shareholders, not consumers.

Consider the incentives. The equity partners at Axiom’s surveyed firms can see that technology makes labor 5x more productive, but don't cut rates by 80%. They attempt to capture as much of the spread as possible.

The Downward Branch of the K

Meanwhile, on the descending branch the 92% of unmet civil legal needs remain unchanged for low-income Americans who still can't afford representation. Eviction defense, family law, debt collection—the legal needs that AI could democratize have diverged out of reach.

The promise of consumer-facing AI tools (DoNotPay, AI Lawyer Pro) runs into the familiar obstacles of quality, liability, and unauthorized practice restrictions. The tools that actually work require legal sophistication to use effectively. Raise your hand if you haven’t heard Professor Scott Galloway’s famous/infamous quote “AI won’t take your job; someone using AI will.” AI is a great tool to assist lawyers but cannot replace lawyers. We see daily examples of that. Pro se litigants using AI to assist in their legal claims often receive advice that ranges from passable, to oversimplified, to dangerously wrong.

And so those who can afford legal help get AI-efficiency. But those who need it for dire reasons but can’t afford it get chatbots with wrong or questionable answers. Unfortunately, they often don’t have the knowledge or expertise to check on the veracity of the answers.

The Hollowed Out Middle of the K

Oxford Economics CEO Innes McFee warns AI will “hollow out” middle-skilled jobs—the roles where tasks are routine enough to automate but not so physical they require human hands.

Law schools still graduate around 35,000 JDs annually. What happens when there are too many lawyers for the work that is taking less time thanks to AI? The least trained are the easiest to replace with AI because AI is most effective at the lower-level, repetitive work. AI cannot replace the judgment and relationship-based work that partners and some senior associates do.

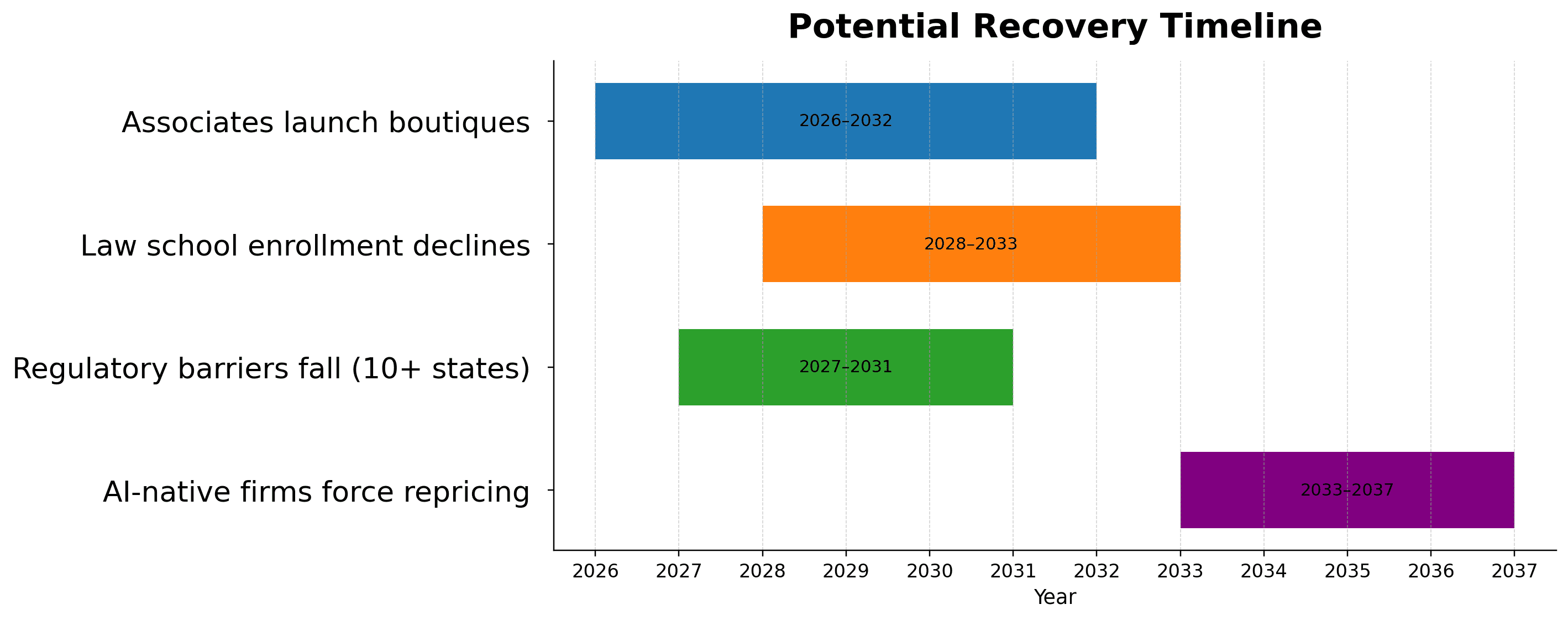

The Timeline

McFee's projection is that the K economy persists until at least 2035. We need a decade for productivity gains to reach low-skill workers before the upward and downward branches converge. AI is not going anywhere, so that convergence requires AI to either (1) dramatically increase wages for non-automatable work, or (2) reduce costs so substantially that services become affordable despite stagnant incomes.

In legal services, neither path looks likely. Wage pressure on court-appearance lawyers will come from the surplus of JDs competing for non-automated work. And cost reductions require firms to voluntarily surrender margin. The billable hour makes that choice optional.

How the Branches Eventually Converge

AI will push legal fees down eventually through oversupply. Economics 101 taught us that when you need one-fifth the labor to produce the same output, four-fifths of your labor force is hunting for work. Desperate lawyers will be willing to discount their services.

For example, let’s imagine a mid-size firm that employs 40 associates and generates $40M in revenue. If that same firm could do the same work with only 20 associates—plus AI subscriptions—to hit the same revenue, partners could keep all the lawyers and find more work, thereby increasing the margins, or let 20 associates go, also increasing margins if the can figure out how to bill the time saved. The 20 displaced associates don’t evaporate. They hang their own shingles. Or they join contract attorney platforms. And they undercut established rates because $100/hour beats unemployment.

But all that market-adjusting pressure takes time. Law school's classes won’t shrink fast enough to prevent a glut, and AI will continue to improve, making the surplus grow. That results in market pressure only gently, slowly easing prices down.

Wealth convergence will require productivity gains to reach non-automatable workers. In law, that’s the court-appearance attorney, the client hand-holder, the human who must physically show up. Their wages actually rise when there’s scarcity.

We’ll also see a surplus of credentialed lawyers competing for shrinking associate positions, flooding into solo practice, undercutting each other to survive. That surplus leads to a buyer’s market.

The top 200 firms will remain largely insulated. Their clients don’t buy legal services—they buy insurance against catastrophic outcomes and relationships with power. They are not looking for and do not want the cheapest legal fees. They want the lawyer who has a commissioner of the SEC on speed dial, or the partner who golfs with a cabinet member.

Wealth begats wealth. The wealth effect matters. When your assets appreciate, you feel richer. You spend more. You hire more lawyers—perhaps at premium rates—to structure investments, minimize taxes, and handle sophisticated transactions. The economy becomes increasingly driven by the financially well off.

Plus, BigLaw operates in oligopoly. Clients can’t easily substitute for cheaper firms. Partner laterals maintain pricing discipline better than OPEC maintains production quotas. AI makes these firms more profitable, not cheaper. So, the branches will never converge.

Where Convergence Will Happen

Mid-market and below—where clients have options and services commoditize, we will see legal fees go down. Real estate closings. Straightforward business litigation. Estate planning for the ‘merely’ affluent. Employment disputes. Contract drafting without nine-figure consequences.

This might benefit small and solo firms most. AI-powered solo practitioners and boutique firms can afford to price their time at $150/hour instead of $350 because their cost structure allows it. They can use virtual offices for virtual meetings and even employ virtual legal assistants. They don’t carry the heavy overhead load of marble-floored offices and inhouse dining.

Another source of pressure is AI adoption by what used to be ‘legal form providers’ like LegalZoom and Rocket Lawyer. They are already pulling the lowest dollar simple consumer work out of the pipeline. And as they incorporate high quality AI, they will continue to pull more and more complex consumer and small-business work away from real live lawyers.

Law firms follow the money. Always have, always will. Practice groups serving wealthy individuals and large corporations boom while legal aid budgets flat-line. The K economy closes only when productivity gains finally trickle down—which takes time.

The Access-to-Justice Mirage

Any empirical evidence for AI expanding access to justice is at best, anecdotal. UC Berkeley's 2024 field study —the first of its kind—showed legal aid lawyers using AI achieved better outcomes with proper support. Encouraging, but this makes existing legal aid more effective. That’s a great thing but does nothing to expand the pool of people who can afford representation.

As mentioned earlier, consumer-facing tools exist, but quality concerns and unauthorized practice limitations constrain their utility. The UK Legal Services Consumer Panel warns that “lower cost AI-enabled services which are not regulated for quality may lead to those with less resources getting a poorer service.”

A justice gap starts looking more like an uncrossable chasm. Where AI is building a bridge for corporations, all it’s doing for legal aid is handing it a longer rope. But there is hope.

The Path Not (Yet) Taken

Could AI eventually democratize legal services? Absolutely. The technology enables subscription models, fixed-fee pricing, and true automation of routine work. But reaching that future requires disassembling or rethinking the billable hour, embracing alternative business structures, and accepting that making legal services genuinely affordable means accepting lower profits. None of that happens quickly, if ever.

It’s an especially steep hill to climb when the path of least resistance is to pocket the efficiency gains (either surreptitiously or validly), keep charging the premium, and marvel at AI’s transformative potential—for partnership distributions.

The promise of AI in my mind was not only faster, cheaper, higher quality legal work, but also the possibility of rewriting the economics of justice itself. We’re getting cheaper, faster legal work, but the economics haven’t changed significantly yet.

Capital optimizes itself first.

© 2026 Amy Swaner. All Rights Reserved. May use with attribution and link to article.

More Like This

Legal Fees Aren’t Going Down Despite AI Adoption in Law

AI has made BigLaw faster and more profitable—but not cheaper. Instead of expanding access to justice, efficiency gains are flowing upward, leaving legal costs high and the justice gap intact.

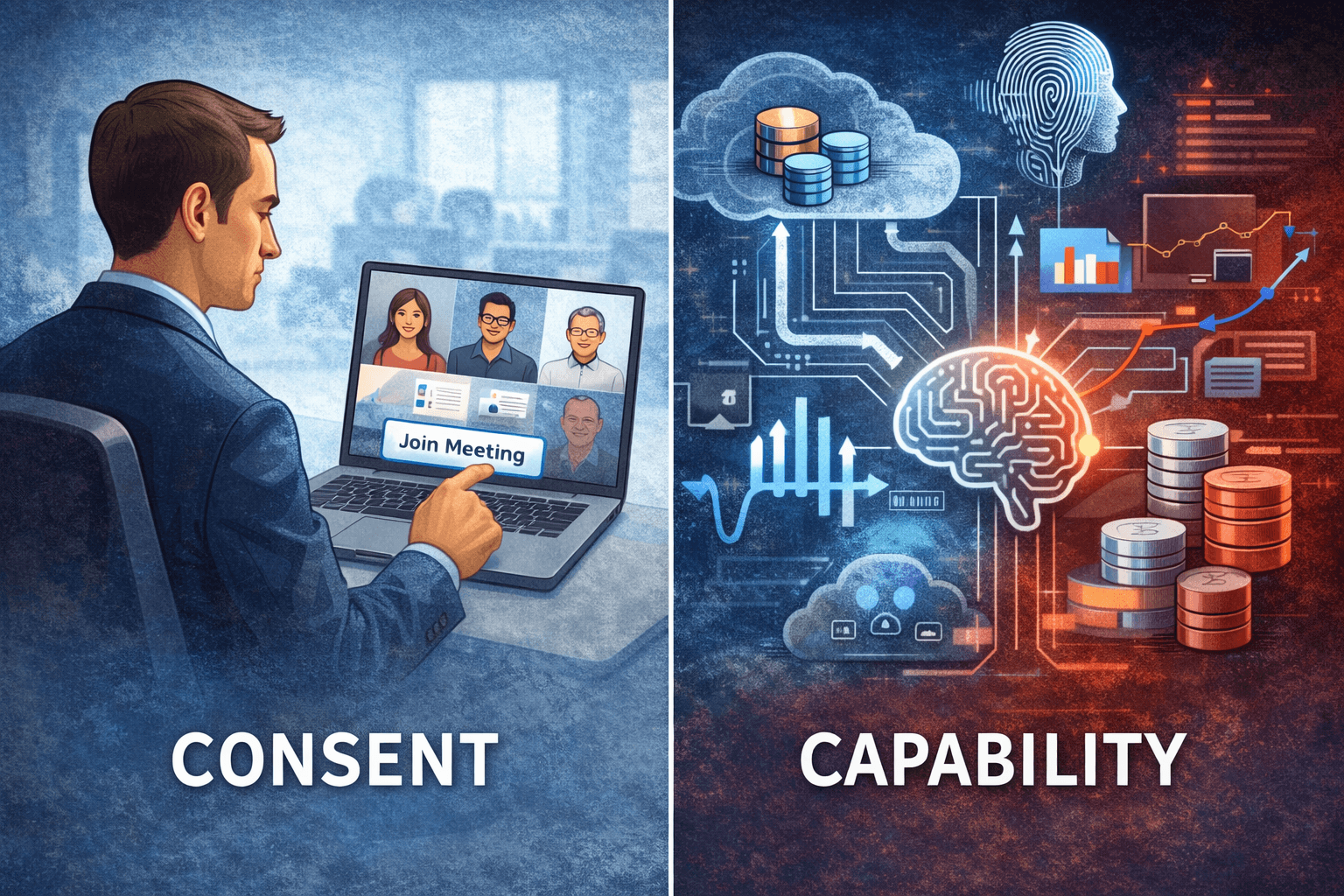

AI Note-Takers, Wiretap Laws, and the Next Wave of Privacy Class Actions

Part 3: AI note-takers deliver real efficiency gains, but when vendors retain or reuse conversational data, they expose every meeting participant to escalating wiretap, privacy, and biometric liability.

Part 2: AI Note-Takers, Wiretap Laws, and the Next Wave of Privacy Class Actions

The same features that make AI note-takers powerful—centralized processing, speaker identification, and “product improvement” licenses—are now forming the backbone of a coordinated wave of privacy class actions.